What Matters Most is Showing Up

On writing with intention, self-trust, and committing to your magic.

A version of this essay originally appeared in Catapult’s Don’t Write Alone series in 2021.

I started my second novel in the spring of 2017, before my son’s first birthday. I got my annual Moleskine (the twelve-month weekly planner with a calendar, extra large, softcover) and slowly, methodically, in a sleepless caffeinated daze, mapped the book. One scene in each calendar square, one scene per day. The novel takes place over the course of six months, and, needing structure, I took myself through it that way, one month at a stretch, one day at a time. The book opens in July, so I started writing in July. One thousand words a day, no matter what.

One thousand words a day: a cliché now, possibly. Sit down every day at the appointed time and aim for one thousand words, and no matter what, try and get there. Take a class with me and this is what I’ll tell you to do. (And also what Jami Attenberg tells you to do, in her much beloved #1000WordsofSummer).

In recovery meetings they tell you to keep coming back even if you don’t want to, because it works. When you can’t trust yourself, you trust the program. Regardless of how well this works for recovery, it works for writing books. What I’ve come to realize over the course of writing three books now—with a hazy idea of beginning my fourth, because every book is different and I’m different, and every time you write a new book it’s the first time you’ve ever written a book, regardless of what career writers say; it’s different and you never know what you’re doing—is that it doesn’t matter so much what you show up with. What matters, mostly, is that you show up.

If a work is yours, you have to keep putting heat on it. Like love.

The first Catapult class I taught was the craft-focused six-week workshop Voice and Vision, centered on getting your bearings as a writer and going toward the light. But there were many other classes with a similar vibe, so the concept didn’t really stand out. Julie Buntin, Catapult’s first Writing Programs director (who has always been the most encouraging and supportive, and to whom I am so grateful) encouraged me to come up with something more results-focused and specific, so I created 40,000 Words in 40 Days, a concept I more or less stole from Faulkner, who famously wrote As I Lay Dying in six weeks while working night shift at a power plant.

If Faulkner can write a book this way, someone else can too. If I can write a book this way, someone else can too. If I can make the best thing I’ve ever made on no sleep, no time, no artist’s life, no fancy residency, and under massive amounts of pressure, someone else can too. To borrow from Giancarlo DiTrapano, legendary publisher of Tyrant Books, If it works for me, it works. And so I thought I’d share a method. Instead of overused shadowy suggestions that presume you don’t know what you’re doing, I wanted to share a system that can always be made available, in spite of/in tandem with external factors, anxieties, and pressures.

You can’t count your anxiety at the end of the month, but you can count your pages.

Half of it is talent; the other half is discipline. The third half is knowing what you’re working for, and I believe—I know—that it has to be more than obsession. Obsession lights the creative fire, but faith sustains it. Faith in what you’re doing, faith in the project to believe in you during the times you don’t believe in it. It’s not about forcing an outcome, or aiming for perfection, whatever that means. It’s about having enough faith in your artistic sovereignty that you’ll rearrange and cut and move as much as you need out of the way to make room for what deserves the space—your art. How much is in your life that doesn’t belong? How many things take up your time and attention that could be outsourced to someone else, or don’t need to be done at all?

When I started drafting my second novel, I was a new mother with no money. I went to the coffee shop every day saying I had freelance work (lying) to spend time with the novel, to outline and draft. In revision mode during high Covid-19, I rented a studio downtown for $140 a month and escaped there to work. The path wasn’t always lit, many times I had no idea what I was doing, but I gave myself the space, trusting that the book would show itself to me if I made conscious room to hear it. I stole inspiration from whatever was around. I read Big Magic in one afternoon while preparing for an endoscopy.1 Everyone takes shots at Liz Gilbert but this book changed my life. If an idea is yours, she says, you have to claim it and not let anyone else have it, and that means steady interaction with the project. She writes about having an idea for a novel and sitting on it too long until the passion died—and then the universe magically transferred the idea to Ann Patchett, who did write the book.

Obsession lights the creative fire, but faith sustains it.

So: If a work is yours, you have to keep putting heat on it. Like love.

With that, I am aware no one likes writing advice in the form of step work, but I have some for you. This is what worked for me, and if you want, it can work for you too.

1. Steal the time.

Take the time you need for your work by any means necessary. Put it on the schedule. First thing in the morning if you can, or whenever a realistic time for you is. Identify it and make it nonnegotiable. If you have an unsupportive family that doesn’t believe in art or work, lie to them. Invent a freelancing job to give yourself permission to disappear for an hour or two, into a coffee shop or your car or the tool shed. There is nothing better than being able to give yourself what you need. Time is a gift when someone else lets you have it, but we’re not about gifts. We’re about entitlement. Become entitled. The book will only exist if you make it so. If you’re into the Tarot, this is all Magician. Give yourself the tools and space you need to bring it to life.

2. Make a constellation.

A constellation is the outline. Many people have this academic type of association with outline, this A-to-B-to-C introduction-body-conclusion model that can feel inapplicable to a creative project at worst, constricting and out of touch at best. While the conventional outline may work for some, it can be difficult (for me, impossible) to conceive of a work’s shape and texture this way.

Think of the outline instead as a constellation, a shape made up of stars—points of light—marked down and drawn together by connective tissue. Imagine these points as the images you already have in your mind, elements you know belong in the story, the hard crystal parts—and the lines that draw them together as the connective threads that create the shape the whole ends up taking. These connective threads are mutable, as there are infinite ways to connect constellations, but it just so happens that the pictures in the sky we know are the ones that have been drawn and named already.

When Charles Bukowski wrote, “Don’t try. Don’t work. It’s there,” I feel that to some extent he was talking about this constellation. If you think of the work as if it exists already and only needs to be uncovered and knit together, bringing it to fruition suddenly becomes much more accessible. Thinking of the work as it is—as a metaphysical concept with an existing form that only needs a physical push—helps you take the spooky uncertainty out of the project and approach it in a more clear-eyed, self-assured way.

Take the time to build it up. Really give the whole of the book some thought. Let it reveal itself to you, in all its light and shadow. The more complete and stable the rough sketch is, the easier the color and connection will be.

The important thing is to build up some structure, but with the goal of retaining freedom. Imagine your outline as the titanium implant that holds a broken bone in place: It’s there for the bone to build around, and whether the implant stays in (the project stays true to outline) or you get it removed (the project deviates from outline), the structure will hold. The implant is not there to cage the bone, but to keep it growing steady.

3. Write the book.

Put your ass in the chair and write. One hour a day, one thousand words a day, five hours, five hundred words, it doesn’t matter what as long as it’s consistent. Take your anxiety to work. I have a shot glass on my desk, and every time I show up with something weighing on me—fear, self-doubt, uselessness, death—I write the feeling on a piece of paper and drop it in the glass, and I let it sit in purgatory while I sit and do my work. Then when I’m done, I take it out. Tear it up or burn it or save it for the next day. You can’t count your anxiety at the end of the month, but you can count your pages. Notice what you’re showing up with and either use it, adjust it, or ignore it. Therapists advise you not to compartmentalize, but sometimes you should.

4. Remember that nothing good gets away.

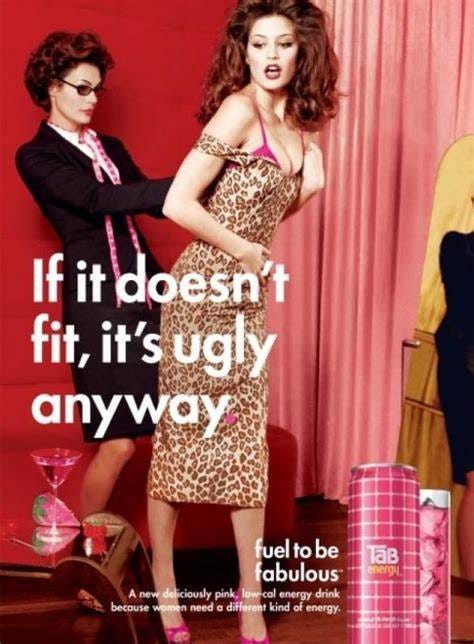

John Steinbeck’s way of saying, If it doesn’t fit, it’s ugly anyway. Applicable everywhere, and always true.

Think seriously about how you want to apply your talent and discipline in this life. Do you write toward the dead? Do you write for self-actualization? For the canon? Do you want money? This is a valid thing. It’s okay to be driven by money, if that’s the type of person you are or the thing you most need at the moment. If that’s it, dedicate yourself wholly to the goal of becoming a bestselling author. Seriously. Don’t wish. Aim for what you want. There’s so much unnecessary back-and-forth about success and money and “selling out” and “making it,” but there are two landscapes: There is art and there is commercialism. There are two different sets of rules and two ways to play the game, and the overlap that happens—a really great piece of art ends up making a lot of money, for example—is both extremely possible and almost always an accident. Of course there are more outcomes than that. You never know what gifts your truest work will summon. Set your goal, know your stakes and commit to the uncertainty of your worldly outcome with nothing but joy.

Don’t wish. Aim for what you want.

The thing you can’t do, ever, is wait. Wait for the right time, wait for the signs, wait for something to fold or make room or otherwise give you permission to begin. In my experience as a master procrastinator, my only reason ever for not doing something was secretly not wanting to. There are so many reasons you can find to not do something. But if you can find just one reason to do it, no doubt you’ll find a way.

Endoscopy prep isn’t so bad when you make a sort of spiritual retreat out of it.

It’s like the universe was all, “You payin’ attention? I’m helping you solve your problems” and then yeeted Mila into my life 🙌🫶

thankyou for this! ❤️