Smokin’ in the Boys Room: Notes on The Stadium Tour

Gina Nutt on post-COVID concertgoing, the strange beauty of collective experience and $8 pretzel twists.

Three buffalo statues graze the green between highway and exit. We set out early this afternoon and though we’re only a few miles from Highmark Stadium, traffic curls and crawls. This is the furthest I have gone from my home in Ithaca, New York since December 2019. The only other journey: a 45-minute expedition to Horseheads, where I adopted a cat. The occasion for today’s sojourn: The Stadium Tour, featuring Def Leppard, Mötley Crüe, Poison, and Joan Jett & the Blackhearts, with Classless Act opening. Originally scheduled for 2020, The Stadium Tour just passed the halfway mark in its 36-show run in major cities across America, with rumors floating about expansion to include a European leg the following year.

The summer has been slow, lazy. A rotation of work, writing, reading, gardening, homemaking. Being home has become an excuse I’m tired of making for myself. So after a month of indecision, my husband and I bought tickets. I like that this frivolous show is a re-entry that is also an escape. Into what, I’m not sure.

Driving over I tear up near Geneva—lush trees on each side of the car, acoustic Tom Petty playing. Miles later, the same song piped in a service station restroom. I take it for fate as I keep restarting the automatic faucet to wash my hands.

Our exit delivers us to more curving roads. We eat the PB&J sandwiches we packed in a cooler with seltzer and pretzels. Arms reach from a Jeep that pulls ahead of our car. Someone looks back at us eating our sandwiches. We turn onto the last road to the stadium. Along Abbott, cars fill driveways and lawns where signs and sandwich boards advertise $20 parking outside houses. Several intrepid residents hawk everything they’ve got to desperate concertgoers—“Yes a bathroom.” Some signs feature the Bills’ charging bison logo and letters in the team’s red and blue palette. Fans pose in driveways, leaned close for photos. They flex fingers in peace signs and devil horns. They traipse the sidewalk and walk in the road toward the stadium. Cars and people on bikes with baskets full of t-shirts congest the stretch that leads us to a lot, where an attendant swipes our debit card as “Cherry Bomb” booms across the street. We rush to find a $40 spot as fast as we can, driving slow enough to mind the tailgaters who have not yet made their way to the stadium. We put on the ball caps we brought to block the sun. I’ve sported a pale purple Bart Simpson-esque chapeau all summer; my husband’s is a last-minute desperation accessory he bought grocery shopping hours earlier, “Ithaca is Gorges” stitched green on beige canvas.1

Crossing the lot, I laugh, nervous to join a crowd. Is this real? We don’t have far to walk, so I don’t have time to overthink before we’re through a metal detector and on a miniature odyssey to find our seats. Through stadium tunnels, down steep cement steps we reach the bench. I’m so distracted looking around I don’t hear what Joan Jett & the Blackhearts are playing. The stands aren’t packed and this is still more people than I’ve been around in two and a half years.

The sun has me glad for my hat, even if now that we’re inside I’m even more certain my husband and I look like losers. I stuffed essentials in the pockets of my denim jacket—hand sanitizer, ear plugs, a KN95 mask, debit card, driver’s license, phone—but I’m getting toasty, so I sit with my coat on my lap, tapping my feet and nodding, but mostly just vibing, which includes unease at the possibility of getting sick. At the same time, I’m glad to be among other people. Isn’t this what we missed? Live music, a shared experience. Almost like an answer, the opening to “Crimson and Clover” fills the stadium like a long exhale, the kind you give when you have something to let go. I close my eyes and fall in the sound. All of me charged, the breeze on my face a bulwark against high-octane anxiety. People sing and this moment beyond my usual orbit takes on tones of joy. My cheeks warm. The blood in my arms can’t keep up.

I don’t feel sad or nostalgic or excessively happy. I feel here, part of something.

Tethered to this happiness is a reminder of lost time—irretrievable days, months, and years. Time that’s just gone. The thought tightens my throat. I well up, thinking tomorrow I’ll wake feeling worse because recognizing what you’ve been missing infuses the absence with new proportions. “Crimson and Clover” reaches its psychedelic bridge. I want to make a joke about finding God at the Mötley Crüe show. Instead, I think of this song playing at points during the last few years. The simple, private joys that stitched together the days. When they play “I Hate Myself for Loving You” two women on the ground pose for a photo together. One has on a leotard, the other a bra and shorts. Both wear fishnet stockings. They’re smiling and dancing, like good friends do. At the chorus, they climb the stairs, toss their heads back, hair streaming behind them like an 80s music video. Joan Jett & the Blackhearts close with “Bad Reputation” and more people rise to dance. Pleasant, poppy, lighthearted.

Between bands people filter in and out of rows. The cans of alcohol and sugar I don’t buy cost $15. Among the cuisine—chicken tenders, fries, hot dogs—I catch a glimpse of a soft pretzel twist wrapped in tissue and decide that will make dinner between the last two bands, Mötley Crüe and Def Leppard.

People on the floor pose for photos. Attire includes: shirts for bands on the bill, leather, fishnet, spandex, denim. More peace signs, more devil horns. They buy beer and water, point at merch racks to indicate which $50 t-shirts they want. I already own shirts for two of the bands, both from the same LA-based company that licenses images to print them on boxy crops with slouchy sleeves and intentional holes.

Among the complex rigging on the ground, the black ballast filled with water inspires some questions: Are we dunking Bret Michaels? Will there be a wet t-shirt contest? A mix of metal and classic rock make up the turnover tunes. Motörhead. David Bowie. AC/DC. The crowd sings along to “You Shook Me All Night Long.” They’re so amped they keep up the communal chant-sing when Poison starts with “Look What the Cat Dragged In.” I’m not dancing or moving my mouth, but the concert camaraderie is undeniable. People have not forgotten how to have fun. As Poison plays, the person dancing behind me follows up every accidental brush of my ball cap by patting my head. A few times he bends near my face to apologize. “It’s fine,” I say. Though I get slightly irritated when it keeps happening because I realize he might not be patting my head in apology, but steadying himself in his revelry.

Bret Michaels plays the harmonica. Joy fills the stands as the crowd claps in sync. Then a singalong begins to “Your Mama Don’t Dance.” Bret hams it up with high kicks and leaps. His bellbottoms, struck with flashes of red, flail at his ankles. He covers his round-the-head bandana with a cowboy hat. The crowd seems enchanted with his downhome way of talking, the conversational tone he takes coming down the catwalk to insist on a good time. He tells us Buffalo was a city to break “Every Rose Has Its Thorn” and even though it’s still daylight some audience members hold lighters aloft as they sing.

The sun has shifted. I’m no longer baking beneath it. Some people are developing sunburns. As afternoon becomes evening, the cement stairs become a cruel challenge to anyone who is not sober. People stumble up, slow and careful. A few times, someone helps steady the climb, leaning partner or pal against them, saying, “Okay, okay, up. That’s it.” The environment is not as crude as it sounds. There are families here. A few parents toting children who sport noise-cancelling headphones.

During turnover for Mötley Crüe, I notice someone on the ground wearing a shirt that says Social Media Sucks across the back. Meanwhile, a seating disagreement takes place down our bench. A voice says, “We’ve had these tickets for two years. They’ve had them for two days.” The voice softens, just a little, and asks, “Who do you like?” Another voice: “Oh, I like them all,” with the certainty of trying to prove something. Until now, I thought no one here really cared. The dancing, the Twisted Tea, the bold, un-ironic sartorial choices: wearing the band shirt to the band’s show, fishnets and daisy dukes, shirtless men drumming their bellybuttons. This posturing—How long have you had tickets? Who are you here to see?—disproves my quaint theory that no one cares or has anything to prove at The Stadium Tour. Of course it means something. Of course we always have something to prove, even if it doesn’t mean much.

Of course we always have something to prove, even if it doesn’t mean much.

Each time a song ends, a hush pauses the audience. I think, Something is happening. Then my husband says, “Something is happening.”

Fog bursts above the crowd. Red, drifting plumes of smoke. A performed news broadcast takes over the jumbotron screens. The key takeaways from the projection: LA emergency, metal, fear. Then, through the smoke, the unmistakable curling whine that is Vince Neil’s voice. The blare of “Wild Side.” The sound is engrossing, blatant and wondrously vile, an in-your-face soundbath of cock rock imploring every last one of us to indulge our inner feral beast.

I don’t want to lift my shirt, yet some part of me does. It’s good to be bad, after all. Bad men, unlikeable women. They aren’t quite the same.

Of course, they’ve brought girls, a trio of professional dancers called The Nasty Habits. They dance and climb the scaffolding while singing into handheld mics. They flip their hair and spin on poles atop platforms enclosed in spikes. The jumbotron pastes up their filtered, grainy faces.

Both “Your Mama Don’t Dance,” which Poison played during their set, and “Smokin’ in the Boys Room,” which Mötley Crüe doesn’t play during theirs, are covers of early 70s rock. “Your Mama” indebted to Loggins and Messina, “Smokin’” to Brownsville Station. Both songs have bluesy undercurrents, both are rock regurgitations, homages to other times, earlier cultural underbellies. Humanity has endured plagues before and more will find us. Even our present state seems defined by the constant flux of variants, ever-changing recommended precautions, updated vaccination guidance.

The evening invites tame degrees of hedonism. The emotional texture of the crowd filling the stadium changes with the bands. The subtle shift from Joan Jett & the Blackhearts to Poison is emphasized while Mötley Crüe plays. The people around us during their set are the most raucous compatriots we’ll encounter in the stands all night. Their dancing is a sloppy kind of sexy. Nikki Sixx comes down the catwalk to speak to the audience. The people behind us shout “Fuck you.” They shout, “Fuck Tommy Lee” and “Fuck Brandon” so it’s hard to hear Sixx. I don’t fully understand my neighbors’ ire, so I face forward and roll my eyes.2

Tommy Lee comes down the catwalk claiming he has seen zero titties the whole tour. Just then, like magic, the jumbotron airs an audience member seated atop someone’s shoulders, broadcasting her bare chest. Another woman does the same. A man to my right grabs at his friends’ shirts, egging them on to flash. His friends tell him he should flash instead and he settles down. Someone coming down the cement stairs reaches into the row ahead of us and squeezes a woman’s butt. She turns to her friend and laughs and the person who touched her looks back to smile at her. Maybe they know each other, but it seems like not. Later, my husband will say that Mötley Crüe brings out the worst fans, or the worst in their fans.

Some glimmers of bad behavior we witness are embarrassing. Others lend an echo of wish fulfillment: someone you could be, someone you aren’t. Beholding the evil twin to our own goodness—“I’m not like that”—or hearing a whisper of a deeply harbored desire. It’s entertaining. I don’t want to lift my shirt, yet some part of me does. It’s good to be bad, after all. Bad men, unlikeable women. They aren’t quite the same.

Later, I’ll follow up the show by reading The Dirt, Mötley Crüe’s collaborative autobiography, co-authored with Neil Strauss. I special order it to the bookstore where I work. It arrives with its red cover, a liquor bottle with a headless woman swimming in the neck. When I sit on our porch reading it, I’ll fold the cover back when someone goes by on the sidewalk.

During “Girls, Girls, Girls” the dancers wear the most clothing they’ve worn all evening—skin-tight biomechanical bodysuits that make them into living robots. Two robo-women inflate from the stage, towering above and framing the band. We take the cement steps as a lengthier-seeming version of “Kickstart My Heart” nears its end.

I join the long restroom line I’d hoped to beat. Someone carrying a red purse cuts the line, joining a woman in front of me. Further back someone hollers, “No, red purse! No!” To which Red Purse says, “I’m standing with my aunt.” The women down the line shout, “Fucking bitches.” As outrage at the name-calling swells, two more people squeeze past, saying “We’re going to puke. We’re going to puke.” One has her hand over her mouth. The person behind me says, “We don’t know if that’s a real puke.” It’s not something I care to challenge. Someone goes into a stall, only to come right back out and ask if there’s more toilet paper. An attendant holds out a full roll. “That’s why you bring tissues,” says the woman behind me, pressing some into my hand. The kind gesture is endearing in its own gross way. The stall fortune assigns me is stocked, so I can lose the tuft of scary purse-tissue. By weird bathroom magic, my benefactor and I end up fighting the same unresponsive automatic soap dispenser at the same time. Parting ways with washed-and-dried hands, I tell her to enjoy the rest of her night.

My husband is waiting for me, leaned against a wall. I’m after one of those $8 pretzel twists I’ve seen people carrying around the stadium. The first concession stand we try is out of them, so we buy M&Ms and head toward our section only to notice another concession stand with cases—plural!—of soft pretzel twists. We wait in line and I get one and it’s down into the depths again for Def Leppard.

My husband made a habit of making weekly record store visits the last few years. A way to keep time and expand our collection. It’s grocery day. It’s record store day, which is actually a holiday once a year. The records he carried home under his arm each week like tally marks on the wall, sundials transmitting sonic messages from the universe into our living room.

“I’m aiding and abetting your midlife crisis,” I tell my husband, even though we share this escape. It’s an upgrade from the week during the summer of 2020 when we paired dinners with music biopics—The Dirt, Bohemian Rhapsody, Rocketman. The week we watched every Twilight film. The Valentine’s Day we rented Fifty Shades of Grey.

We had tickets for a Sebadoh show that got cancelled. When the refund landed in our bank account, the pandemic seemed infinite. The concert had been booked at the Haunt, a divey bar living its second life in a pocket of Ithaca waterfront near the Farmer’s Market. Within the last few years, the building housing the Haunt got bulldozed to make room for a development project. At the Haunt, I’d seen Bob Mould, Beach Slang, Wolf Parade, Guided By Voices, and several iterations of Ithaca’s all-day December music festival, Big Day In. The ghosts of those shows and many others went in the water below the dock. For this show, we were easily upsold on any small reassurance that there were still some things we might be able to control—or at least get refunded—in our lives. The Stadium Tour tickets with insurance cost $250 each.

Tethered to this happiness is a reminder of lost time—irretrievable days, months, and years. Time that’s just gone.

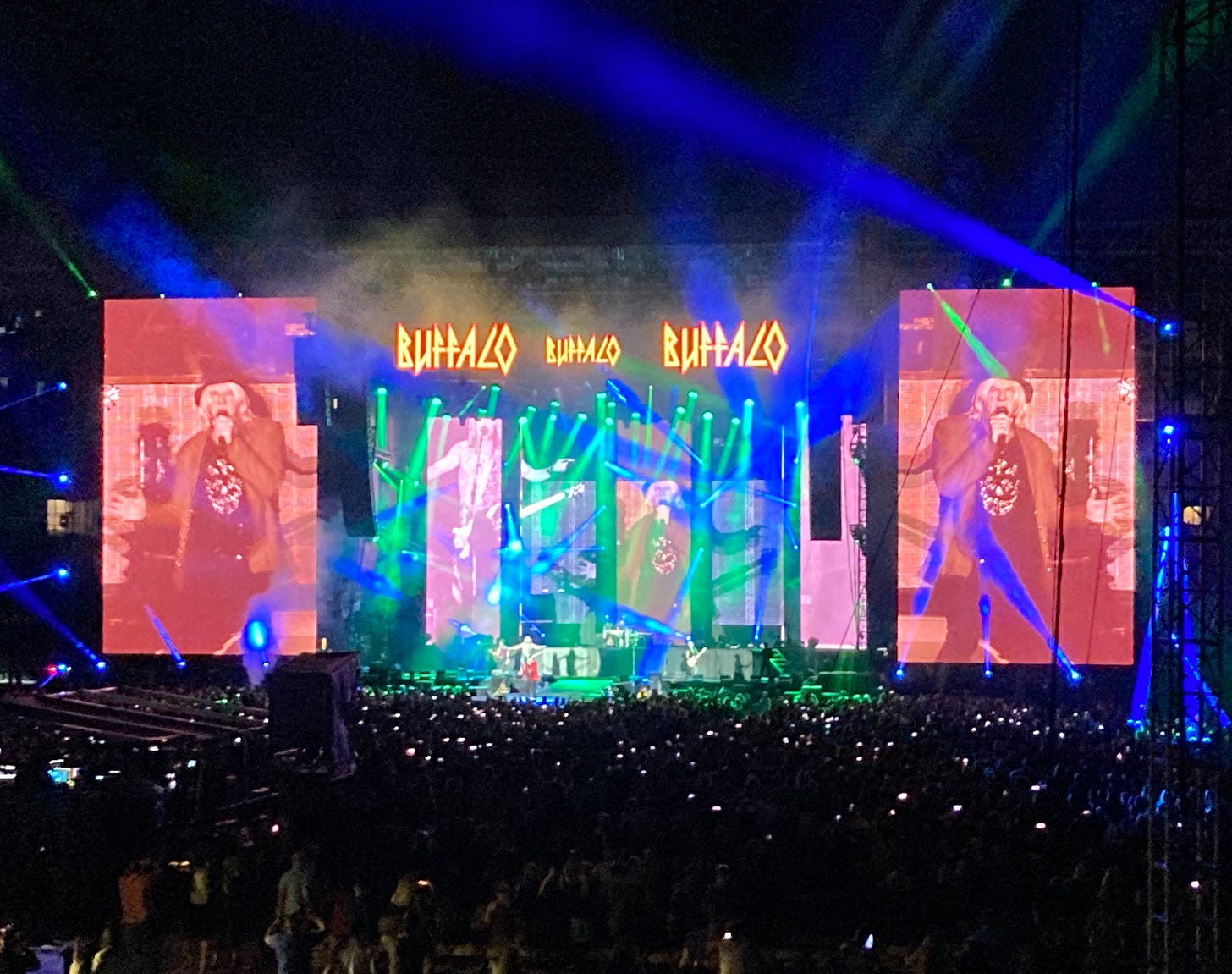

We eat our M&M-and-pretzel-twist dinner. The jumbotron displays a countdown while we wait for Def Leppard. The moon is full, or almost. She’s round and low over the stadium. The clock reaches the last ten seconds. The crowd counts back like we’re waiting for the year to turn over, the rest of our lives to begin. Def Leppard emerges alongside an impressive laser light show.

Having woken at 4:45 a.m. I’m exhausted, and yet amped on adrenaline, noise, and lights. I yawn, blissful, dissociated; a content lobster in a microbial pot. The crowd is gentler. Less rowdy, but still excited. Warmly loving and electric. The people in front of us aren’t the same people who were there during Mötley Crüe. They’re a couple mouthing the words to “Rocket” at each other, bopping their heads, quaint compared to our previous neighbors. Nostalgia pulls through the stadium. Laser lights snap at the dark and dance through the air. Def Leppard plays new songs they wrote during the pandemic and the lost time I mourned earlier feels like time spent another way.

Amusement park graphics dance across the screen behind the band as they play “Animal.” A digital rollercoaster car snakes from a clown’s wide-open mouth, crosses the stage and gets smaller. The cool night air washes over me and reminds me of late summer carnivals, the New York State Fair, nights I used to never want to end. This is a night I do and don’t want to end.

Def Leppard ends the night with “Photograph.” Blown-up digital Polaroids spin and set atop each other, one at a time, until they fill the screen. Backstage footage, past tours, studio time, fans across decades. The man who patted my head has left. The aggro-bros have left. My husband says, “If you want to dance this is the last one.” I lean into his shoulder, watching the photos accumulate on screen. I think of mornings I’ve placed a teal riser on my office floor and cued up a playlist, a fitness habit I took up during early lockdown. I scrolled through photos those months, seeking reminders of life: trips, dinners, ping-pong in our friends’ backyards. I cried at our happiness, how sweet we didn’t know we had it. I made virtual visits to a haunted house and a natural history museum. The online tours distracted me, though the emptiness on set pinned fresh despair to the days. Bare stairways, empty halls. The watchful taxidermy animals, oblivious to what was happening. Even if they’d been alive, they’d have been indifferent to our human suffering. One evening, I saw two friends walking their dog in a parking lot across the street. I waved from my kitchen window even though they couldn’t see me. I wanted to run out to them, barefoot, but stood crying at the sink. Was it the same mechanism of my mind that sensed Something is happening before the red smoke billowed, the same gear that heard “Photograph” and felt tenderness toward the images? It’s a warm ache that swells within and around me. Purple and blue-white lasers streak the dark. I don’t feel sad or nostalgic or excessively happy. I feel here, part of something. Among people who put on years of tour shirts, made any small gesture that we, collectively, missed this, even if the sentiment is a postcard some feel tired of receiving, a reminder of our ongoing uncertainty.

We are surrendering to what we don’t know.

We are learning the new shapes our lives have taken as the shapes find their forms.

My husband and I jog up the stairs to get out before the crowd. Security has locked the entries, so we join the line of concertgoers all exiting through a single turnstile. The line grows behind us as we step closer. I feel like something is about to happen.

“Let us out,” people shout, rattling the bars with their fists.

“Open the gate.”

Gina Nutt is the author of the essay collection Night Rooms (Two Dollar Radio). Her writing has appeared in Denver Quarterly, Forever Magazine, Joyland, Ninth Letter, and elsewhere. She lives in Ithaca, New York.

Studying photos after the fact, he will declare himself “not a hat guy” only to bring said hat on a nine-day vacation to Southern California.

A few days later I ask my husband if he made out what the people behind us were yelling when Nikki Sixx came up. He thinks it was “Fuck Hillary.” In 2017, Tommy Lee took to the internet to verbally skewer then-President Trump and the voters who cast ballots for him.