I am writing this book because we’re all going to die.

—Jack Kerouac, Visions of Cody

On April 2nd, I finished the one-millionth revision of my manuscript. I felt happy and accomplished for exactly two minutes before realizing with a grim trepidation that I would have to read it again.

But would I? I am aware that I’m a card-carrying perfectionist. I will tweak a thing to death and still find things to tweak well after it’s done and out. Maybe I was just hesitant to take the next step. Maybe it was my Virgo ascendant. Maybe I had no idea what I was looking at anymore and another pass wouldn’t help.

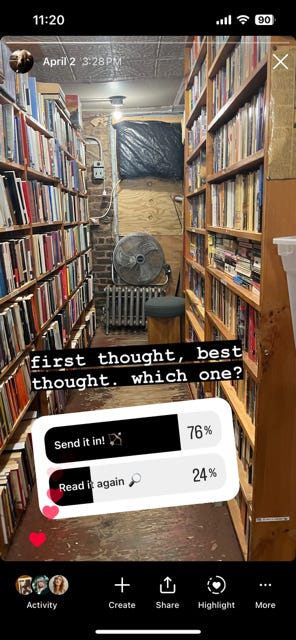

I decided to ask Instagram.

By the time the poll ended, “send it in” had won by a wide margin. Tempting. I looked at the respondents. One of the votes was from my agent, who chose “read it again.”

I scrolled all the way back to the top.

It always takes so much longer than you think. So. Much. Longer. My students’ faces fall when I tell them this, and I’m starting to think I shouldn’t. But I like to share things I wish I’d known when I was new, and it’s not a big secret, that you can’t hack this. There aren’t any tricks. It’s just you and your mind and any stamina you’ve got. That when you start writing a book, you sign on for the long game.1

And that it truly doesn’t matter to anyone whether you do it or not.

Not yet, anyway. But that’s where the necessary delusion unshakeable faith comes in. It doesn’t matter yet, but it will matter. Eventually. You have to bet everything on this. You have to know, in the basement of your soul, that your work is divinely green-lit. In the akashic records. It’s what will sustain you over years of rejection and nothing.

Growing up you’ve been taught not to build a castle in the sky, but what can you do, if that’s where the blueprint is?

It’s much easier not to be working on a novel—I sometimes hear novelists speak of a work in progress as an all-consuming crisis—but the ease of not working, after a while, feels cheap: “this life lived only for myself takes on a certain lightness that I find almost unbearable.”

—Elisa Gabbert, “Why Write?” [ref. quote: Ann Patchett, “Writing and a Life Lived Well”]

On May 25th, I got out of bed—sick—and oozed around the house. I sat on the balcony in my robe, shivering in the 80-degree afternoon, and read Ghost Lover by Lisa Taddeo while my son read Max Meow: Cat Crusader in his little papasan chair. I had planned to send in my manuscript the day before, and I hadn’t sent it in. I was supposed to be done, and still there was more. I retreated to the bedroom and lay in the dark for a while, marinating in headache, feeling the minutes creep by. Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. 3 p.m. doom descended. There was no way I was going to feel better. I got dressed and went to work.

I needed coffee, but there are no viable coffee shops nearby. Starbucks is a drive. The local spot downtown was off limits that weekend on account of some festival-parade that would have made parking impossible. Panera was there, in the strip mall, but I hated Panera. I went anyway and walked out as soon as I walked in. It smelled horrible inside, like a hot rush of fetid breath from within a popped balloon. I despaired briefly, cursing the stupid one-horse town with its stupid one-horse prospects. There was a fancy grocery store across the lot, with a cafe. Fancy grocery store cafes are underrated writing spots. I went there.

The cafe was hidden in an enclave offset from the store. A clean, well-lighted place, blissfully empty. I annexed a table and arranged the four emotional support drinks I’d bought at self-checkout—water, seltzer, kombucha, a bottled oatmilk latte. I swallowed two Excedrin with the “as needed” afternoon dose of state-sanctioned amphetamine. Here we go, I thought. System override. I opened the laptop.

But then, I made the mistake of checking my email. Sometimes it just happens by accident, tapping the app out of mindless habit. I didn’t intend to check my email right then, but that’s what I must have done after texting my husband, because all of a sudden, there it was, on a sunny Saturday afternoon: We regret to inform you that your submission was not selected. It was from a residency I really wanted, telling me as kindly as possible that they had 327 applicants and someone among them was a more compelling choice.

I knew it wasn’t personal or indicative of anything, but I was upset. I’d only applied to one other residency this year, which I’d also really wanted, which had also said no. Aside from the prickle of mild offense at the rejection itself—the undigestible idea that someone else’s work was, by some measure, better—I was upset that I’d wasted my time. I’m not a serial residency applier. I usually don’t even bother with them unless I think I have a) a good reason and b) a good chance. I was sure I had both. I shed a few tears in the empty cafe and went to a dark place for a moment, staring into space. Then I looked at my manuscript, cursor blinking.

What the fuck.

The first fictions writers create are the fiction of the writers they become. Realistic self-assessment is the first victim of a life making meaning.

—Stephen Marche, On Writing and Failure

The residencies were of the memorial variety, established in honor of influential literary figures. Except I’m almost positive their namesakes would have laughed at the idea of any institution being set up in their honor. Both were famously anti-institution. Both were visionaries. Both were iconoclasts. They were nuts, they took risks, they were brave. And both would have said to me, Why? Why waste time and money appealing to some committee so you can write? Just write.

One of them I knew in real life, and I know for sure that’s what he would have said.

My husband, meanwhile, reminded me that early validation wasn’t important. I didn’t need to be reassured that I was writing a good book. What I needed to do was write a good book. And then get out of its way.

Moby-Dick was a commercial failure, out of print by the time Melville died. The year Fitzgerald died, he sold a total of 72 books—across all his published works. James Joyce—James fucking Joyce—author of impenetrable masterpiece Ulysses, couldn’t get a job as a fucking adjunct.2 Bulgakov didn’t live to see The Master and Margarita published. We know what happened to Van Gogh.

All of them knew their work mattered. None of them got to know when, or how much.

On May 26th at 3:08 a.m., the exact time my son was born, I hit send on the final revision.3 I closed the laptop and sat in the charged silence. Took the dogs out, the moon waning gibbous. A snowy quartz sphere. I let the dogs hunt in the glow of the fireflies. I don’t remember when I fell asleep.

Unless you’re Kerouac and can bang out a stunner like On the Road in three weeks. But even then, it took six years to get published.

The better he wrote, the worse things seemed to go for him, according to Stephen Marche. Although it’s true that for some reason, getting a job as an adjunct is bizarrely difficult.

I later discovered that May 26th is also Stevie Nicks’ birthday. She was born at 3:02 a.m.