Primal Decorations and Renewal

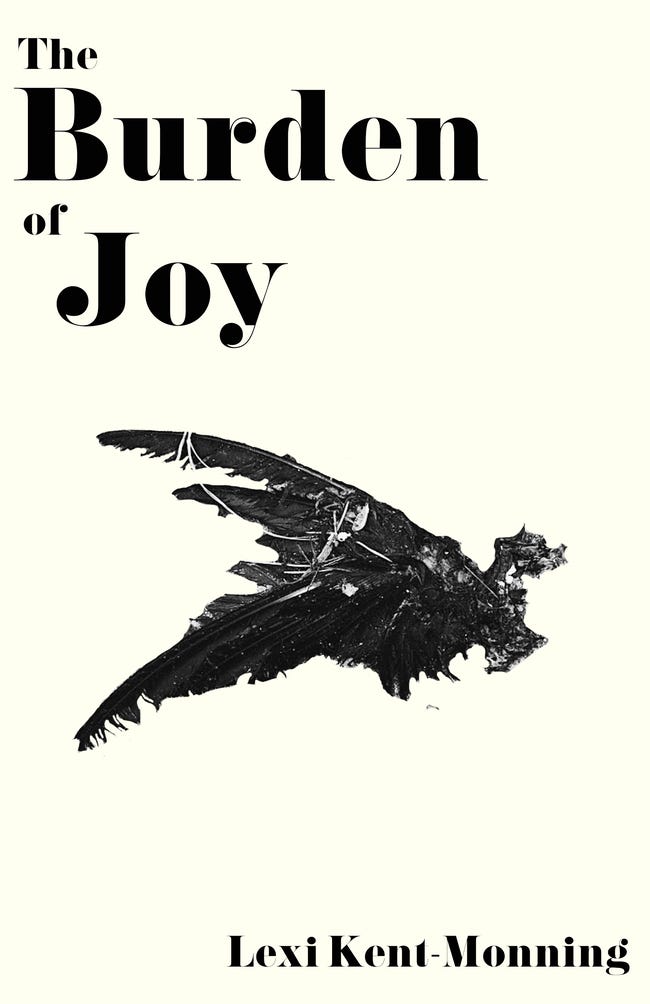

Gina Nutt reviews Lexi Kent-Monning's THE BURDEN OF JOY.

☆ Come see Gina Nutt and Lexi Kent-Monning read with Madison Jamar and Catherine Spino in an all-Black Lipstick lineup at the Miss Manhattan Reading Series!

Monday December 4th @ 7:30 pm / Niagara NYC ☆

Shelving books at work, I’ll sometimes quip about what’s selling. I’ll say, “The octopus is having a moment” or “The sea is having a moment” or “The mushroom is having a moment.” A personal favorite is woman versus void. It’s a private joke I keep to myself, flipping to a passage in Sheila Heti’s Motherhood before I quietly place the book on the shelf and return to the register. I’ve come to carry these books in my muscles, reaching again and again for stories in which women confront the edges of themselves on a precipice of change.

I’ve wandered domestic voids, professional voids, romantic voids, and voids of childlessness; voids of pregnancy, birth, and motherhood. Illness voids. Grief voids. Family voids. Friendship voids. Yet these qualifiers negate the very definition of void—empty space.

An incomplete list of loglines describing several favorites: woman transformed by a makeover follows her pill of an academic husband on a life-changing safari; woman fucks a frog man; woman shuffled off to an unusual rest home by her shitty kids has a surreal adventure instead of becoming bitter; woman born with stomach in literal knot; woman followed by black hole that adapts to her moods; woman about to undergo experimental cosmetic surgery that will reverse all her former procedures spends pre-op eve reflecting on pivotal relationships in her life. I love how these women live on the page. Smart, tuned into their desire, in some cases eccentric, in every case wholly themselves. The narrator in Lexi Kent-Monning’s mesmerizing and introspective debut novel, The Burden of Joy, joins this lineage of truth-seekers as she traces the end of her marriage and immerses herself in the possibilities for renewal that reveal themselves when our most meaningful bonds collapse.

Perhaps “the void” is my shorthand for “something isn't quite right” in someone's life. The void symbolizes unrest, unease, a seismic shift. Through an emotionally exacting carousel of vignettes, Lexi, the eponymous narrator, draws out her life after her husband of twelve years leaves her. The accumulation of lean chapters creates the effect of beholding a photo album. “Staircase,” for example, details Lexi and her husband Daniel’s first meeting: “He was ascending it as I stood on the top step and we immediately started talking as though in mid-conversation, effortlessly, joyously.” Familiarity, comfort, and a sense of liftoff infuse this scene—two lovers meeting on a staircase—even though we know their marriage does not last. We’ve already seen the end of their love—in the opening chapter, Lexi finds Daniel with another woman at a New Year’s Eve party—when we witness the bright affection of this brief, cinematic moment.

Chronology and setting pivot from chapter to chapter, mirroring recollection: present to past tense, one city to another. Place also serves as an emotional barometer. Lexi’s journey is set against discordant backdrops. The rich, sun-and-ocean-drenched beauty of the California coast juxtaposed with its ecological precarity. New York City’s glittering appeal against its ominous gray skyline. Place also contributes to the book’s momentum. The Chicago getaway Lexi takes on her own, where Daniel later takes his new girlfriend. The MDMA-fueled tryst in Upstate New York where Lexi indulges with a new lover using her share of her and Daniel’s honeymoon money, a psychedelic flood of drugs, feelings, and sweat.

Meanwhile, atmospheric details ground us, as in the descriptions of Big Sur and the Carmel Highlands cabin Lexi and Daniel move to after leaving Los Angeles. Lexi recalls from her youth: “The first time I smelled marijuana was in Big Sur, sitting in the river in a giant wood chair, reading a chapter book about a witch child who made her own elixirs to heal people. I thought I was smelling one of her healing ointments as I read about them, so mysterious and herbal.”

Lexi is a healer, a giver. She helps Daniel find work at a commune in Big Sur and the job highlights an increasing emotional distance between them. When the replacement of the Pfeiffer Bridge makes the commute undriveable, Daniel decides to live at the commune. The emotional separation between them becomes physical. Lexi has violent dreams and this violence bleeds into her days. She finds dead animals in the woods near her home. Chiseled sentences anchor us within the book’s momentum and shifting memories. Sharp, startling details characterize Lexi’s life alone at the cabin: “I began stumbling on the dead almost daily. First a mangled snake on the beach, tangled into itself over and over again. And then the raccoons, birds, deer, mice, frogs, a fanged, fish, lizards, a butterfly, squirrels. All left to rot, just like me.” Each animal like an ominous card in a foreboding tarot spread. The earthy details are the comedown and counterweight to the staircase meeting, brutal symbols of the end of the marriage. Recalling mishaps surrounding the move to the cabin—broken pottery, an injured worker—Lexi shares a hesitation to read too deeply into these events: “I didn’t admit to myself that these seemed like bad signs. I was sick of signs, exhausted from intimating higher meanings from everything.”

I’ve wandered domestic voids, professional voids, romantic voids, and voids of childlessness; voids of pregnancy, birth, and motherhood. Illness voids. Grief voids. Family voids. Friendship voids. Yet these qualifiers negate the very definition of void—empty space.

This is the struggle at the heart of the novel: Lexi keeps showing up for people who keep disappearing.

If California points to death spirals, then New York City offers renewal. Lexi makes an electric connection with a man named Leo while visiting the city for a friend’s wedding. The day after they meet, she makes a trip to the Guggenheim Museum. Wandering the halls, she observes: “The colors, textures and themes are in unabashed harmony with my night under Leo’s grasp. I’m mercifully free of thought, and instead full of senses and instinct: I touch the velvet couches, inhale my unwashed hair, Leo still emanating from it.” The museum offers Lexi a transcendent experience after her separation from Daniel, a lush, sensory world full of hope and pleasure that contrasts with the sense of death and loss surrounding the Carmel Highlands cabin. The rebirth it signals is luminous and satisfying. “How will they all know that I’ve been resurrected?” Lexi wonders as she walks through Central Park after her sublime museum visit.

As a narrator, Lexi is a relentlessly sharp witness of her tendencies. Her self-awareness compelled me to stay with her, along for the ride wherever she took me: when she writes Leo a thoughtful letter after returning home, a poetic account of their trip upstate and what it meant to her, which he does not answer. When she questions whether it was the truth or the drugs that influenced his past confession of love, yet still makes additional trips to see him. During one of these visits, headed to a party on her own, Lexi considers the sex marks on her body: “I always find a kind of pride in primal decorations.” Throughout her emotional stumbles and triumphs, I’m as in as she is, because she knows what she’s doing, she knows what she wants. Her pursuit of pleasure is central to the nuanced themes the book raises about connection: Are we hedonists when we indulge our desires? Are we selfless or foolish when we care for others? These questions become harder to answer as Lexi describes lounging around her sublet with Leo as “the height of intimacy of my life. More than a marriage.” Yet, as the intimacy increases, Leo backs away. This is the struggle at the heart of the novel: Lexi keeps showing up for people who keep disappearing.

This throughline follows her back to California. Daniel visits the cabin and Lexi realizes she no longer desires these routines with him. Following this revelation, she tries to give herself a home. She cooks food she likes instead of Daniel’s favorite meals. She removes his home decor. Redecorating is not without its challenges though, as she learns when deciding how to fill the bare walls: “After more than three decades on the planet, I still don’t know what to put on my walls that I would like to look at every day.” Lexi revises her life and fills in the blanks. She pawns her wedding ring and a pair of anniversary earrings. She reads an article about a man who created a disconnected telephone booth to talk to his brother who died in a tsunami. He calls it his wind telephone, because the words he speaks are carried by the wind. Inspired by this concept, she buys a green rotary phone and transforms Daniel’s closet into her own wind telephone booth. She does this so she can speak to people she feels she can’t speak to directly. These events have the intensity of rituals marking enormous shifts for Lexi. Yet I also appreciate the glimpse they offer of her imperfect attempts to move forward, as when she reflects upon mistakenly calling the wind telephone her "ghost phone": “Actions continuing towards me instead of me carrying them out externally; a haunting instead of a confession.” I feel haunted alongside her because the changes she’s trying to make are more complicated than trying a new recipe or changing the art on her walls. These are edits that uproot the being.

The tension between Lexi’s efforts to put herself first and her instinct to care for others culminates when Daniel shares his plan to move to the East Coast with his new partner. After tearful deliberation, Lexi selflessly sends their dog, Ladybird, with them. When Ladybird is gone and the fire department trims the largest redwood on her property bare, Lexi decides to move to New York City. Instead of the move symbolizing a death or a failure, it’s a relief: “I know I spent my time here trying harder, at everything, than I ever have.” She realizes it’s no failure to stop trying to make the unworkable work.

As usual, the move to New York City is fraught: a delayed move-in, lost belongings, a difficult landlady. Unsure where she’ll make her next home, Lexi packs only clothes, a few beers, and a wooden box containing the ashes of her and Daniel’s first dog, Rufus. The ashes comfort her: “When I close my eyes I can still feel his fur and hear the rhythm of his arthritic walk and the jangle of his collar…I can feel his personality, his being.” The memory of Rufus and the box lend Lexi a tender bond in an unstable moment. They’re also evidence of her commitment to keep close what matters to her.

In refusing a scorched-earth divorce story, The Burden of Joy reframes the split, orienting our attention toward Lexi’s grief and longing. This approach offers an honest portrait of reeling, whether we’re falling in love or confronting the fallout of a lost bond. The result is a book that gorgeously refracts exhilaration and despair with a blazing interiority dialed into the complex nature of connection.

During a harsh and revelatory reckoning with her self-awareness, Lexi recalls the night she met Leo, when he insisted Daniel was an idiot for leaving her. “But I know that the idiot is me,” she says. “I can’t give up on the men whom I have to convince to love me. I don’t even try to give up. I double down, I fight harder, I pull out stops that will haunt me later.” She owns this, visiting Leo before he leaves on a cross-country road trip. True to her character, Lexi gives him a thoughtful farewell gift: a lucky penny from his birth year, which she begged several jewelers to drill a hole in, before finding one who obliged her request.

Having finally made her home in New York City, with Daniel and Leo in the rearview, Lexi reflects: “I’ve never been important, but I would like to be taken seriously.” I’ve carried this confession with me since I first read it, the wisdom in wanting nurturing to matter.

There is no moral judgment, no failure in offering love that goes unappreciated. Lexi doesn’t condemn or reject her instincts. Instead, she decides to offer herself the care she has selflessly shown others throughout her life. In doing so, Kent-Monning’s debut expands the landscape for the narratives of nurturers with its unique blend of tenderness, desire, rage, and love. In refusing a scorched-earth divorce story, The Burden of Joy reframes the split, orienting our attention toward Lexi’s grief and longing. This approach offers an honest portrait of reeling, whether we’re falling in love or confronting the fallout of a lost bond. The result is a book that gorgeously refracts exhilaration and despair with a blazing interiority dialed into the complex nature of connection.

The void is not a void after all. It’s a space where lives get lived, tangled, sorted. A space where we can witness the possible lives we could live. How vulnerable we can be, how tender and alive. The void’s “moment” may well be defined by its shrinking, the decreasing empty space in which these stories float, the constellation taking shape.

OMG this sounds so good. Purchasing immediately!