Parallel Worlds: Plumbing the Depths with Emmalea Russo

Can we separate the artist from the art? Yes and no.

Mila Jaroniec: The sensory descriptions in Vivienne are so vivid—the book is an immersive experience, a world unto itself. How did you conceive of the correct structure for this novel? Or, how did you know when you’d found it?

Emmalea Russo: The story came to me in a flash and I drafted it in a feverish fury, then kept working and reworking. I wanted to set the story up with jolty momentum using internet comments, then cut to Vivienne and her quieter life in Pennsylvania while she’s unknowingly going viral. Parallel worlds: the zap and slip of internet rumor mills and the sensuous world of matter. The book needed to happen at the speed of virality while also being stuffed with dreamlike, slow-mo, snowy moments at home. Then there’s the ending, which is a discreet world of its own. The ending came to me much later—hopefully a leap that sheds weird light on what precedes it.

MJ: I loved all the internet sections, especially when they quietly morphed into poetry. And they were so true to life, which made them funny and relatable, but at the same time disturbing and sad. I feel that art is morally neutral in itself—it couldn’t exist otherwise. Why do you think people demand morality from art and artists, the same way they would from politicians and religious leaders? What is it that people are seeing in a work, when their first response to it is shock and offense?

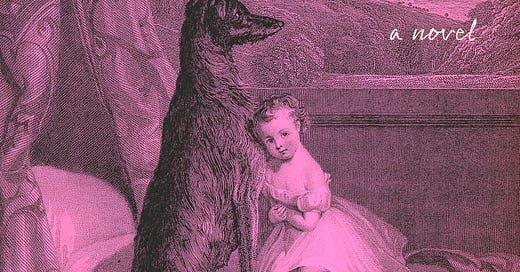

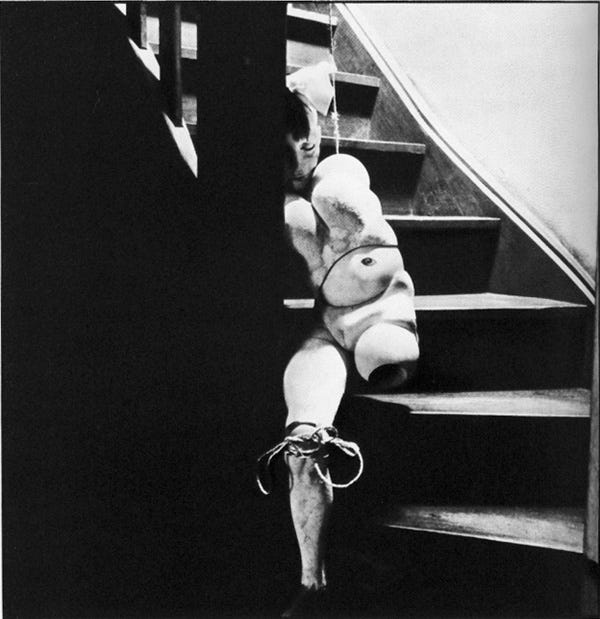

ER: This is a great question. I’m glad you loved the internet sections. Can we separate the artist from the art? Yes and no. I think Vivienne tries to engage this question from a few different angles. Vivienne Volker gets canceled for her alleged involvement in Wilma Lang’s suicide and for the controversial nature of her own work. She grapples with repentance and guilt—what she owes herself and God vs. what she owes the public.

We live in a culture now where people are encouraged to be prosecutorial and managerial. Some corners of the internet are like free-floating HR departments. Not very groovy. People have been trained by the free-floating HR department to assess cultural objects based on their problematicness—almost eager to be offended. Perhaps this is just one moment in the cycle of the spectacle society. In the 90s, Howard Stern tried to give a woman an orgasm over the radio by humming into the phone. Now, he has Kamala Harris on the show.

In terms of shock and offensiveness, we should be offended by art. It’s not the artist’s job to make us feel safe or affirm us. That said, not all shocking art is good.

In terms of shock and offensiveness, we should be offended by art. It’s not the artist’s job to make us feel safe or affirm us. That said, not all shocking art is good. If we sat with our shock, and actually read and thought about the work, we’d get to know it in a different way and our minds might expand. But that takes time. Social media encourages everyone to have a hot take ASAP. Complaints get more hits.

MJ: Art-centered narratives seem to be perennially popular, but sometimes it feels as though people appreciate stories about artists so much more than they appreciate the art they’ve made. Why do you think that is? I’m always here for the stories, but novels like yours—complicated works of art in themselves, rather than conventional narratives whose themes are merely art-adjacent—are miles ahead of so much of what’s out there.

ER: One of the characters in the book, a gallerist named Lars Arden, wants to show Vivienne’s work before he’s even seen it himself, because of the hype surrounding her. I think we tend to gather around images—star machines and cults of personality—more than works. Maybe this was always the case, but now, it’s truer than ever. How do our images reveal and/or cover what they’re depicting? I was thinking about this a lot while writing Vivienne. The book is filled with references to real and fictional visual art, as well as dream images and our schizophrenic visual culture. I think about that line from Derek Jarman’s film Blue a lot—“pray to be released from image.”

MJ: You’re an established poet, but this is your first novel. What unique challenges did writing in this form present? What were you most surprised by?

ER: There is poetry in the novel, and many of my books of poetry contain prose—but writing a storyline, with an arc and characters, is a different substance. I was surprised at how attached to the characters I became, how wrapped up in their inner lives, and how they’re still with me.

MJ: I know you love them all, and probably connected with each of them differently at different times, but overall, who was your favorite character to work with? Or, I should say, who surprised you the most?

ER: I may have had the most fun with Lars, cause he’s a riot. Reverent and cynical. A kind of bitchy, fashionable spiritual seeker who is also a climber. I liked taking him out of the city and putting him in this place that was so foreign to him, shocked and humbled by the bizarre Volker-Furio-Bellmer household. I won’t give away the ending, but the leap that Vesta [Vivienne’s granddaughter] made surprised me, as well as her devotion to the dead, which seemed to imbue her with this relentless bravery.

Creating art and being part of the art world are very different things. They only sometimes bleed into each other.

MJ: What are your thoughts on quitting art, the way Vivienne did? Just stopping the whole train and taking another path? I fantasize about it sometimes, I’ll be honest. Do you ever want to quit, and if so, what parts of the game? And what pulls you back?

ER: I’m drawn to dramatic breaks, quitting, stopping, getting off the train. Vivienne Volker left the art world and stopped making art. She speaks about how she didn’t like who she was back then. She becomes religious, repents, and works as a seamstress. Decades later, which is when the book opens, she gets dragged back into that world through the internet. Creating art and being part of the art world are very different things. They only sometimes bleed into each other. How does our era deal with art and artists from a different one? I think a lot of artists, including myself, experience this impossible tension, which is something the book deals with: a push-pull between the desire for connection and visibility, wanting one’s work to reach people, and the desire to hide, retreat, quit.

MJ: I feel like they do go hand in hand—the need to connect and the impulse to disappear. It’s like…we’re driven to soul-bare, to strip ourselves naked down to our bones, but then an uncomfortable awareness of that nakedness creeps in.

ER: Yes. But also the process itself: the retreat that’s necessary to write, and then the act of putting it into the world. Plus, the fact that everyone now is expected to be their own PR machine, which requires a totally different energy than writing the thing.

MJ: How do you know when you’ve been understood?

ER: There’s no way to really know, right? I don’t think being understood is the goal. The goal is to make something people can’t get out of their heads—meaning, there is something there to come back to, something ungraspable. Do artists even understand their own work? Though, I get a hot, tingling, floaty feeling in my body when I feel grasped or seen. An inner glimmer.

MJ: As a professional astrologer and poet (a true renaissance woman!) and now a novelist, in what ways did astrology assist you in your writing practice, if any?

ER: I feel more medieval than renaissance! I work with a lot of artists in my astrology practice and we talk about how their star charts can inform/inspire/assist their art practices. I feel so saturated in celestial language, so my work must be soaked in it, even though I don’t have a specific practice around it. Vivienne is set (mostly) during one week in late December, so I was thinking about the sun around the time of the winter solstice: waning light, long nights leading up to the shortest day of the year. The decline of the light mirrors Vivienne Volker’s. The sun is the original narrative.

MJ: Now for some frothier questions! Favorite perfume? Fashion designer? Style of architecture? Lipstick?

ER: Perfume: Angel by Thierry Mugler, launched in 1992. Designer: Margiela, especially 1990s-era. Style of architecture: Gothic. Lipstick: None. But when I’m feeling glum, firecracker red.

MJ: What would you like to be asked in an interview, that you never have been?

ER: Marry-F*ck-Kill? Three dudes from the novel.

MJ: Okay, but now you have to answer it.

ER: I have asked an impossible and obnoxious question. But, this morning, I’m thinking: kill Hans, F Lars, and marry Lou. That could change tomorrow. I also have affection for the ghost man that haunts the halls of Vivienne: Vesta’s dad, Max Furio.

MJ: Three words to describe what you’re working on now?

ER: Total fucking lunacy.