The modern gourmand perfume has been laden with cultural baggage from its inception. Ever since Mugler’s blockbuster fruitchouli Angel burst onto the scene in the early 1990s, a perfume that seemed more flavour than fragrance, gourmands have stubbornly remained associated with desserts despite niche forays into more savory territory. This sweet tooth tendency has always invited a host of disapproving views. A dessert fragrance is never allowed to be just a confection. No, the sweet gourmand is a marker of crass and jejune tastes; it panders to the desires of teenaged girls, immature women, and effeminate men; it is an indulgent panacea for those gripped by diet culture; it is a security blanket for a post-Covid society in need of comfort and escapism (as if other perfume genres are not equally escapist).

It’s hardly surprising then, that the current resurgence of gourmands has come with a wave of apologists. Today’s gourmands, we are meant to believe, have “grown up” with novel grainy, nutty, and lactonic accords. A litany of uncommon notes—rice powder, toasted almonds, chantilly cream—are listed in these articles as evidence of the genre’s maturation. See? It’s not just about sugar anymore. This defense is trotted out in spite of contrary evidence where notes like caramel, honey, and marshmallow continue to rise to the top.

Most contemporary gourmands remain confectionery in nature as the industry churns out candied releases across all price points and consumer segments. Think Tom Ford’s Vanille Fatale, Margiela’s Afternoon Delight, Kayali’s Yum Pistachio, Marissa Zappas’ Annabel’s Birthday Cake or Sabrina Carpenter’s Sweet Tooth, the last of which drives home the point with a bottle that appears to be a chocolate bar rendered in Millennial pink. And while today’s It scent, Maison Francis Kurkdjian’s Baccarat Rouge 540, is not technically a gourmand, it is its overdose of burnt-sugar ethyl-maltol that has catapulted it into blockbuster status.

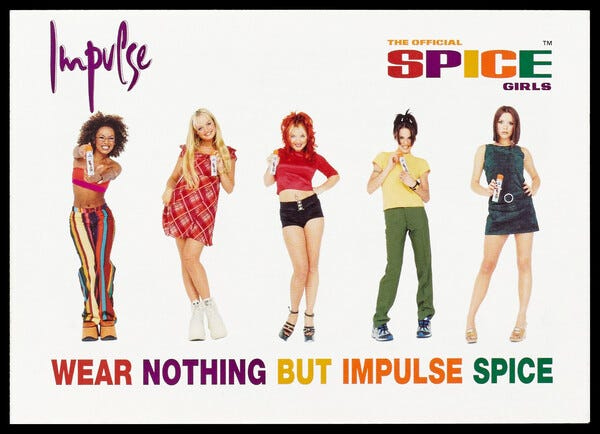

For Millennial consumers, the gourmand is a saccharine double punch. It not only comes pumped full of reassuringly sweet accords, for a generation raised on the aforementioned Angel and Bath & Body Works Warm Vanilla Sugar, gourmands also deliver the sticky lure of nostalgia. It is the olfactory version of a Spice Girls reunion tour, a Mean Girls musical. The generation that grew up with the gourmand is the same one fueling its luxury reboot today. It’s yet another sign of this generation’s scarlet letter of extended adolescence.

If both the Millennial and the gourmand remain unable to grow up, mired in syrupy batter and garish food dyes, coquettish as cupcakes topped with sprinkles and swirls of frosting in spite of all the feints toward sophistication, I would suggest this is not necessarily just a sign of infantilization. For any refusal to mature brings with it potential critiques of everything wrong with maturation. After all, there’s an element of sharpness, even aggression, about so much sugar.

In reconsidering the gourmand, I am not so interested in the genre’s potential to move beyond desserts but in its potential subversiveness. Because so much sweetness may suggest that it’s better to burn out our palettes on sucrose and choke on sweet cream than to submit to what adult life amounts to in our era of extreme capitalist exploitation, rising fascism, and a global climate collapse. Perhaps growing up today demands a saccharine force that is capable of fighting an increasing sense of bitterness and bile. It calls for hard candies and sugar crystals that cannot be dissolved away by the daily vitriol that comes with merely existing online.

In this way, the contemporary gourmand may go beyond notions of innocence and comfort, of cozy childhood kitchens and pleasing baked treats. Perhaps it’s also the scent of quiet quitting—it’s rejecting the traps of hustle culture, involuntary minimalism, and other Millennial coping strategies; it’s refusing to be shamed for enjoying another avocado toast. Forget giving up on home ownership and defined-benefits pensions, we are now being failed by the promises of tech innovation, higher education, and liberal democracy itself. And at a time when dystopian futures are being made present, the resurgence of the treacly, insipid gourmand may show us exactly the kind of perfume our society deserves.

Also by Kawai Shen:

Smelly Old Things

I grew up in a cohort of women who divided perfumes into a patriarchal binary: fuckable, or not. Us fuckable girls were too young to recall the fragrance industry as anything other than a multinational marketing machine churning out a pink-hued sea of generic fruity florals, tooth-rotting gourmands and synthetic aquatics. The rest of fragrance history e…

I enjoyed reading this! Critical engagement with perfume is a new line of inquiry for me and I appreciate the idea of investigating trends in the frequently ignored sense of scent. I like how hopeful + utopian the idea of potential subversive nature of perfume is, but I also feel like it's hard to imagine it as anything but a "millennial coping strategy".

I'm going to take this as permission to go back to bathing in Body Fantasies Cotton Candy. Please and thank you.