“I am almost certain I am free.”

Sophia June reviews Cristine Brache’s GOODNIGHT SWEET THING.

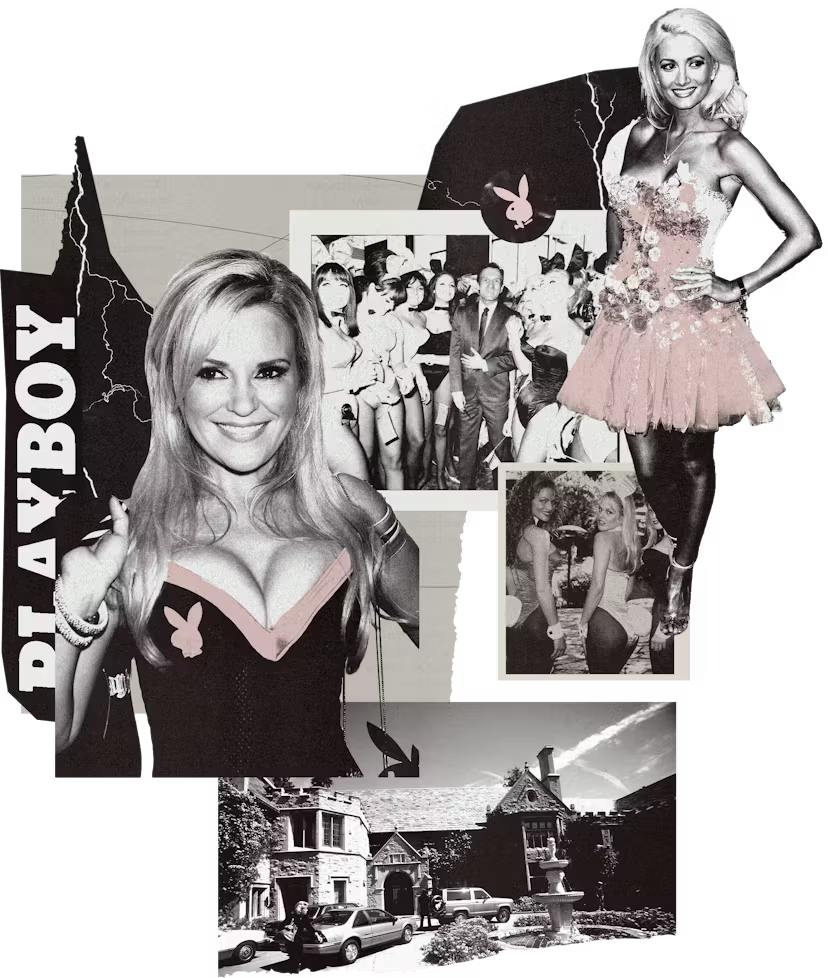

Three years ago, I interviewed Hugh Hefner’s former girlfriends Holly Madison and Bridget Marquardt, who starred on E!’s The Girls Next Door, about their paranormal experiences living in the Playboy mansion for a feature in NYLON Magazine. The women had all kinds of spooky stories to share, ranging from flickering TVs to seeing ghosts dressed in athleisure. But the most persistent threats came from the living.

“I would hide in the bathroom,” Madison told me. “You never had a moment alone. It was the one place in the house where nobody would go. Sometimes the toilet would flush by itself, and I always thought that was kind of weird. It always came during these weird, introspective moments. I don’t know what they were trying to tell me.” (Madison talked to Hefner about her experiences, but he was “not a believer.”)

In middle school, I was obsessed with The Girls Next Door, bingeing it for hours on the E! network, which for some reason was included with basic cable. I remember being fascinated by the episode where Bridget hires a paranormal investigator, who found “high levels of paranormal energy” in various parts of the house. (He also found higher levels when he placed his ghost-detecting machine over the women’s asses.) Even then I could sense that talking about ghosts in the Playboy mansion was just an easier way to talk about the dual nature of the place, the sinister forces at work in those hallowed hallways—to reveal that underneath the boob jobs, Juicy tracksuits, and mandated hyperfemininity lay something darker.

It’s my own interest in that duality—the glamor and grimness of artifice and objectification—that draws me to Cristine Brache’s work.

There’s a natural intersection between Brache’s art and poetry and the world of Playboy: both explore the meeting points of beauty and violence, the ideal of a feminist utopia and its bleak realities. “The Eighth Deadly Sin—Female beauty,” Brache writes to encapsulate the trifecta of power, danger, and objectification, themes that show up constantly in Goodnight Sweet Thing, her second poetry collection, which also includes her out of print debut collection, Poems (Codétte, 2018).

Brache also shares my fascination with Playboy—the epigraph of Goodnight Sweet Thing is a poem by former Playmate Dorothy Stratten, written before her tragic death at the age of 20:

“It’s here, everything—

Everything anyone ever

Dreamed of, and more.

But love is lost:

The only sacrifice

To live in his heaven,

This Disneyland

Where people are the games.”

My own artistic preoccupation with liminal spaces—with the areas in between things—is a large part of what makes Brache’s work so resonant. In my own fiction, what I find most interesting to explore is the moment before the moment—someone walking through a door is more significant to me than what they say after they walk through it. I am drawn to the synapses, the chasms, the slippery, shadowy no-places, where characters don’t yet know if something is just beginning or is already at its peak.

Brache’s work is primarily focused on exploring liminal spaces between performance, idealization, and impenetrability. Earlier this year, she made a series of arresting paintings inspired by Playboy Bunnies. The women are blurred and ghostlike, like they’re fading from the canvas, or fading into it. This blurring of consciousness is also on display in “Bermuda Triangle,” a 2023 installation of a Super 8 film she made of a partially submerged couple kissing in a pool. Using a selection of the film’s stills, Brache made paintings on silk of the stills’ photo negatives. The figures are washed out, defamiliarized to the point of vanishing and being transformed into new figures at the same time.

This fascination with liminal space started in childhood, when she began exploring it by chasing near death experiences. In a recent interview with Allie Rowbottom for the LA Review of Books, Brache discusses enjoying the feeling of proximity to death as a teenager, echoing the spectral force her poetry collection possesses:

“When I was 13, my friends and I would take Freon out of the central AC unit in my house in Florida. We would fill whole garbage bags with it, tie the end with a rubber band, and inhale. My lips would turn blue and I would pass out. The passing-out part is what remains interesting to me because I realized later that I was having near-death experiences, especially because I remember that my periods of unconsciousness felt very long.”

Like Brache’s paintings, her poetry is full of imagery capturing women in various candid and cornered positions with a blurry dualism, masterfully illuminating all the in-between places of youth and maturity, life and death, sleeping and waking. “Once I drew the room / Now it erases me,” she writes. It’s this dualism that she inventively probes in Goodnight Sweet Thing, a confessional aggregate collaged from TMZ headlines, pillow talk, YouTube comments, diagnoses, and sweet nothings to create a lyrical meditation on mortality, performance, objectification, pleasure, and psyche.

Lately, I’ve found myself hiding out in the in-betweens. I recently left a job in media and am two weeks away from a deadline on my first novel. I’m about to move into an apartment alone for the first time, caught in a triangle between my old apartment, my new apartment, and my boyfriend’s apartment, which I’m staying in while he’s upstate at an artist residency and which has left me with more quiet, contemplative time within a stressful transitory one. Right now, I’m in the moment before the moment.

It was utter absorption into the poems that kept me suspended in my own duality.

This might explain the uncanny pull the book had on the mechanics of my own personal geography. I read Goodnight Sweet Thing in almost a single sitting while crossing the Manhattan Bridge on the B train twice. I didn’t mean to. I took the train from Midtown to my friend’s apartment in Prospect Lefferts Gardens, but had gotten on the wrong train and instead ended up in Sunset Park. I looped back, but again took the train going the wrong way at Atlantic, delivering me back to Grand Street in Chinatown, where I’d begun the day at my boyfriend’s apartment. Anyone who has made errors like this knows that at a certain point you surrender to the lost time and try to transubstantiate it into something creatively usable—time on a train is, after all, a small sacrifice to live in this heaven (to borrow a phrase from Dorothy Stratten).

For me, it was utter absorption into the poems that kept me suspended in my own duality—between each side of the East River, between traveling and arriving, between the known world and something stranger and more beautiful, Brache’s words: tall tales of America, consequences etched onto a body, surrendering skin, musings on becoming a “successful object,” near-certainties. See, Brache’s poems came during these weird, introspective moments (to borrow a phrase from Holly Madison). I don’t know what they were trying to tell me. Maybe something about surrender.

In the titular poem, Brache writes:

“We dreamt of flowers and listening to women.

Still, every time

we go to bed,

We go to war.

Sleep

Drowns

In the arms of a fall angel.

Maybe she’s been nauseous since January

Like me

I forget,

Tomorrow

We can wake up without pain

And if I could sing you to sleep,

I would.”

What Brache accomplishes in Goodnight Sweet Thing is a tightrope feat. She effectively captures the duality of life both as an artist and a woman, suspended between beauty and ugliness, pleasure and pain, ultimately surrendering to the in-betweens. This place of surrender puts her in the greatest position at all: She can fade in or out; she can go wherever she wants; she will always have our attention.