Fluctuations

Barrie Miskin on inherited body dysmorphia, toxic 90s diet culture and the beauty in setting yourself free.

I was six when my mother became obsessed with the Jane Fonda workout. I did it with her, circling my little arms until they ached and squeezing and releasing my glutes. A few months after mom began The Workout, she got pregnant with my brother. Daddy must looooove my new body, she said, rolling her eyes. I didn’t understand what she meant, but I loved her body, too. I tried on her clothes, a silky ivory slip, a soft and worn t-shirt with an apple on the front. I thought they were glamorous. When I asked to wear them, she shrugged and said, Sure, you’ll fill it out. Your belly is probably as big as my boobs. I looked at her breasts curved out over her flat stomach and then back down at my little first-grader gut sloped atop the waistband of my leggings. Already, I knew we weren’t built the same.

According to my mother, her body was once legendary, and I don’t remember a time when I didn’t know those legends by heart. They were like bedtime stories that had been whispered into my tiny ears since the day I was born. In junior high my mother walked into choir class in a ribbed turtleneck and the entire bass section stood up to cheer. In college, her boyfriend told her he wanted to play chess on her midriff. At her wedding, my mother weighed eighty-two pounds. “Everyone thought she was my child bride!” my father would say, shaking his head, embarrassed but pleased.

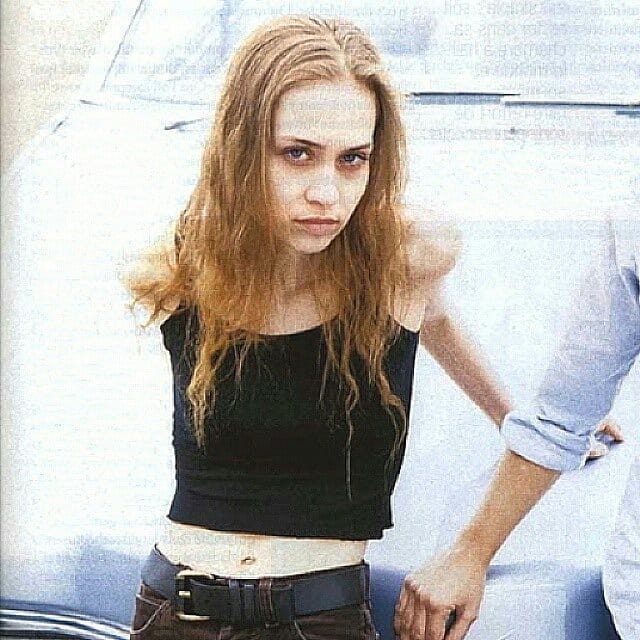

In contrast, I took up too much space. In junior high I felt too loud and clumsy for the hushed circles of girls that turned their backs towards me when I approached. Too big to join activities where my body would be on display: sports teams, plays, a capella groups. I couldn’t run a seven-minute mile or fit into the plaid miniskirts the field hockey girls wore. The shimmering gold slips worn by the a capella singers would have pulled in all the wrong places. Instead, I sat in my bedroom, lost in books, shipping myself with male classmates, lying on the floor by the boombox late into the night, pressing Record each time a favorite song came on the radio. I watched the clear Maxel spin in the cassette player while the hollow eyes of Kate Moss and Fiona Apple and Hope Sandoval stared down from where they were Scotch taped to the wall.

I grew into my role as wing woman, standing on the sidelines as my friends collected phone numbers from boys with low-slung pants and skateboards tucked under their arms. I’d fish another Newport Light out of my pocket and chew on the straw of my cola Slurpee as I observed the transactions, waiting until they were done so someone could give me a ride home.

I looked happy, ordinary, beautiful even. And I wasn't supposed to look that way.

When I went to college, it was the late 90s in Buffalo and raves were still a thing. The bounty of Ecstasy going around was dopey and cheap. Suddenly, I had everything I’d ever wanted—pure love in a capsule of fine powder. I barely needed food. I became ethereal and lovely and small, a creamy slice of belly peeking out between my UFOs and tank top, the delicate curve of my collarbone beneath small wooden beads.

I fell in love. He would stare into my giant pupils and tell me how beautiful I was, rubbing cucumber melon lotion from Bath & Body Works between my fingers. I smiled back, the lotion slick and cool in my hands.

It couldn’t last. We had to graduate, get jobs. I moved home to New York, where the rave had been over for a long time. Still, I was determined to keep the party going. There were other fine powders to try, these ones colder and mean. My hipbones grew as sharp as the clicks my boots made on the frozen January sidewalks when I walked home at dawn, alone.

I grew enthralled with the power my new body gave me. All I had to do was show up, sit down, smile, and I could have anything I wanted. The problem was, I didn’t want much anymore.

My friends paired off and I worried I would never find my mate. My mom pointed out actors on TV that she imagined me with: Seth Rogen, Jonah Hill, Jon Favreau. She thought I might be their type. By this time, my body had relaxed. My cheeks rounded, my belly bloomed, thrilled to return to its natural state. I tried to fight back: I ran, I swam, I clocked hours on the elliptical. I was keto, I was vegan, I was fasting for sixteen hours and eating for eight. I spent four hundred dollars on Nutrisystem, counting the minutes until I could savor the end-of-the-day ice cream sandwich, flattened from the delivery box and as big as my palm.

I didn’t end up marrying a man who resembled the actors my mother had chosen. I married a man who is tall and lanky, with crystalline eyes. At our wedding, I floated down the aisle on the shimmering intro to “High” by The Cure. I weighed one hundred and forty-seven pounds. I was beautiful and light.

The young teenagers I teach now celebrate their bodies, decorating themselves with pastel crop tops and gold necklaces as thick as ropes, long neon nails and tiny rhinestone stars affixed to their temples. They make no excuses, no apologies. They wave and bloom like fluorescent sea anemones in the deep floors of warm oceans. They fill me with love and admiration and envy.

This past June, my mother began driving to Queens to drop boxes off at my house. Each week I watched her make her way down the hot sidewalk. At barely five feet tall, the boxes overwhelmed her frame, now thickened by the unforgiving passage of time. She refused help, complaining about the lack of parking. Inside the boxes were suitcases of silverware, my old elementary school report cards, children's books, overstuffed photo albums, a light switch cover with my name hand painted in pink bubble letters, an oxidizing menorah.

My husband, my daughter and I live in a small apartment where the only storage space is a bedroom closet and a hallway at the top of our stairwell. But my mother was relentless with her weekly deliveries, and I was annoyed.

“Where are we going to put all this?”

“We need to empty everything out,” she said, lightly manic. “The realtor needs to stage the house. She says the market is HOT!”

Her urgency was lost on me, but still, I stretched my arms out to accept the boxes. I shoved them into the small corners of our apartment.

In the late evening, I sat cross-legged on the floor and pulled out the photo albums. The old pictures slid out of their plastic film, the adhesive inside dried up long ago. I moved forward through time. Me as a baby in a highchair, a gummy smile peeking through a face full of butternut squash. Me with ribbons tied around a thick ponytail, riding away from the photographer on my tricycle. Me in a pink tutu, holding a wand topped with a star.

The young teenagers I teach now celebrate their bodies, decorating themselves with pastel crop tops and gold necklaces as thick as ropes, long neon nails and tiny rhinestone stars affixed to their temples. They make no excuses, no apologies.

The years passed. I saw me cradling my baby brothers, a trip to Disney World. A 90s pre-teen with bangs sprayed into the shape of a cartoon cloud. A photo of a high school freshman fell to the floor, body folded inside an oversized Champion sweatshirt, Levi’s and long hair, big gold hoops. I looked happy, ordinary, beautiful even. And I wasn’t supposed to look that way. I’d heard judgments about my body for almost my whole life. They took place in silent spaces: behind the turned backs of the field hockey girls, in the bored glances of the boys outside the 7-Eleven that passed over me and landed on my pretty friend, during the brief pauses of my mother’s legends, stories that would never apply to me. All that time, I was beautiful.

And I still am. I am soft now, round and full. Friends and family and still, sometimes, strangers will comment on my beauty. It is not the sharp and dangerous kind anymore but the beauty of a mother, of someone who is loved.

In the late summer afternoons, I bring my daughter to the playground. Her tiny calf muscles flex proudly as she climbs the ladder of the slide. She stands straight, shoulders back, blonde curls blowing into halos. I imagine that she will never have to worry and the wish washes over me, a salty, cleansing wave.

this is incredible and so beautifully written 🤍 I really appreciate this, thankyou so so much for sharing

Ah, the 90s. All those tiny, beautiful girls. Gwen Stefani's abs were what killed me. I spent high school thinking I was fat, likewise discovered the magic potion that was E, etc. Looking back, tiny body+enormous eyes is a look for cartoon heroines, not a woman. Here's to bodies that are lived in.