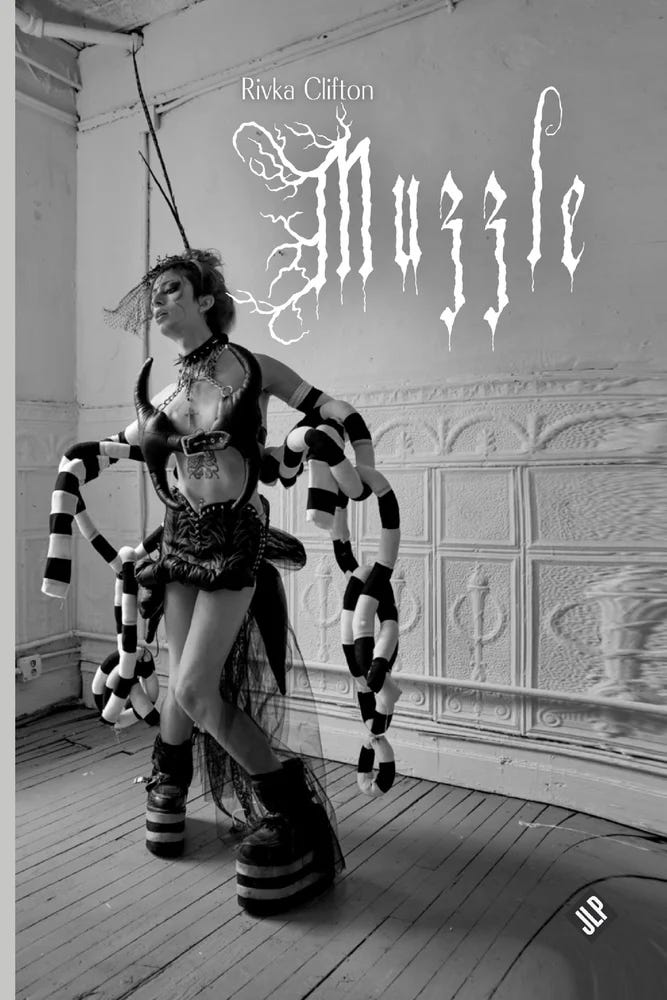

Disassociation and Embodiment with Rivka Clifton

C. E. Janecek and Rivka Clifton on violence, animality, self-knowledge, and Clifton's debut poetry collection MUZZLE.

My earliest conversations with poet Rivka Clifton were about how poetry is a series of power dynamics. Not just between the writer and the page, but the reader and the book, the poems themselves in conversation with one another.

There’s a hypnotic circularity to Clifton’s writing, bringing the reader into intimate conversations between lovers, families, hunters and hunted. Clifton recognizes this interconnectedness through the fluidity of nouns and pronouns. The work may engage with definitions, but never allows itself to be tied down to one meaning or another.

When I received an early copy of her debut collection, Muzzle, I opened it to four definitions of the title:

muzzle

muz·zle

(n) The opening at the end of the barrel of a firearm; the end part of a gun barrel nearest to its opening.

(n) The projecting part of the head of an animal, including the nose and jaws.

(n) A device, usually an arrangement of straps or wires, placed over an animal’s mouth to prevent the animal from biting, eating, etc.

(v) To restrain from speaking; to impose silence on; to suppress the message of.

There are many titular poems, each of them reimagining the meaning of the muzzle. The muzzle that barks and the muzzle that silences, a weapon’s muzzle that strikes the muzzle of an animal.

I immediately knew I wouldn’t just be reviewing this book. I’d need to talk to Rivka about it.

“It’s a surreal mix of sadness and goofiness. So if you’re inhabiting that space, it’s for you.”

C. E. Janecek: How would you pitch your debut collection, Muzzle, to readers?

Rivka Clifton: I like this question. I’m a serial Lex poster and I’ll talk to people about this book and say, “It’s a surreal mix of like, sadness and goofiness. So if you’re inhabiting that space, it’s for you.”

CEJ: I love how different that sounds from all of your blurbs.

RC: Yeah. I think with blurbs you have to have this air of seriousness or importance, and that’s never something I can do for a long time. I can manage it in short bursts.

CEJ: On the topic of publishing, you have two previous chapbooks: MOT and Agape (Osmanthus Press). How was writing and publishing a full-length collection different? What did you learn from the process about your writing?

RC: MOT is a long poem in fragments, and originally it was supposed to be a part of Muzzle, but in the editing process it kind of didn’t fit there anymore, so it was just hanging out and I didn’t know what to do with it. Osmanthus Press is based in Wuhan, and it’s run by my friend Jon Miller. He wanted to get into chapbooks and asked if I had something ready so he could learn the ropes before he started with strangers who might be less forgiving of any mistakes. So I sent him both MOT and Agape. Agape is also a selection of poems from a longer book.

I find short-form works and chapbooks incredibly difficult to do. I’ll write a full-length manuscript and then identify which poems can be touchstones for it and then cull it that way. Maybe the question for me specifically would be, how is writing a chapbook different from what I normally do? It’s hard because in a chapbook, you have to achieve everything a full-length book does, but quicker and faster. I don’t know how you write, but when I write, I usually don’t have larger themes or concepts in mind. I have images or situations that I want to look at and it takes me a while to put two and two together to figure out where my brain is going.

CEJ: I very much relate to that process. If anything, I’m unlearning from grad school the urge to force poems into a larger narrative. I want to be able to write freely and then organize in a more organic and intentional way—shaping the whole book as a final product, rather than trying to shape poems that I haven’t even conceived yet.

RC: Yeah, yeah. I think that’s where a lot of difficulties come in with that artificial environment of grad school, where you have a captive audience and you have to write a certain number of pages per semester, building it all into this final project. It’s just not how writing works, for the most part, outside of a program.

“I feel like pronouns share this weird space, where they’re at once what we refer to ourselves with and what others refer to us as. They’re a meeting spot between self and other.”

CEJ: Now, to get into Muzzle itself, one of the first things I noticed about your collection was the ephemeral nature of language. The relationship between pronouns and who they signified seemed intentionally loose. For example, in “Tar” (21), the “he” made me wonder: Is Clifton speaking to the ex-husband? The Devil? God? Masculinity? Can you tell me more about your decision to sometimes obscure the subjects of your poems?

RC: In the beginning stages of drafting, when I was going through the editing process with Jen Harris and Richard Siken at JackLeg Press, Richard actually asked if I was invested in the different pronouns and what describes whom. Do we keep them? Do we want to square them up more? Do we want to make them intentionally loose?

The decision to obscure the subjects of the poems came about because the more I thought about it, the more I became invested in this collection blurring the distinctions between victim and perpetrator, person with power and person without power, and seeing what can happen when we complicate those binaries. How we relate to an action, how we relate to a situation.

When editing, I was really taken by this craft essay by

, “What Writers Really Do When They Write.” He writes about “ambient intelligence,” where you make all these little changes, and somehow, collectively, they give a work a little more complication, a little more nuance that you couldn’t engineer intentionally. I think that with the loose pronouns and their obscure subjects, my editing process naturally fed into this ambiguity of situations, the perpetrator/victim dichotomy.CEJ: In our cultural and political landscape, “pronouns” have become a synecdoche for trans people. Can you tell me more about the fluid use of pronouns in your poems? Do you see it as being part of this larger conversation about our culture?

RC: [Laughing] Yes, I’m one of those pronoun people. I guess I’ll start this out with a little joke on myself. I have another manuscript called Beast-Headed, which is what the chapbook Agape comes from. I wrote it while I was still in the closet to myself and the whole manuscript is from the perspective of a trans woman who lives in my apartment and does everything that I do and knows everything that I know and then I’m like, “Okay, what? Why? Why am I doing this?” In my experience, the writing knows me more than I know myself in a lot of ways.

I wrote the majority of Muzzle between 2012 and 2014, so a lot of this was before the whole scare about pronouns. I feel like pronouns share this weird space, where they’re at once what we refer to ourselves with and what others refer to us as. They’re a meeting spot between self and other, which is always fruitful ground to play in.

CEJ: Wow, speaking of Beast-Headed and poetry revealing more about us than we know—I remember reviewing Stephanie Burt’s 2022 collection We Are Mermaids, which is a love letter to herself and to other trans women. I was managing editor at Colorado Review at the time, and I found out we’d actually published her first collection, Popular Music, back in 1999. I returned to it, wondering if, as a reader, I would see any traces of the future Stephanie in the book. And yes, the very first poem is an ode to womanhood.

RC: That’s so good. I have one more story about that. I really like Burt’s essays, especially this one on elliptical poetry. I would read it and reference when I was in my MFA. One of my professors tried to dissuade me from Stephanie Burt’s work by saying “You know—” she didn’t gender her correctly— “You know [she] wears women’s clothes…”

CEJ: Oh my god—imagine using that as an argument to discredit anyone’s art.

RC: I think for a lot of trans people, poetry and art give a safer, lower stakes place for us to engage in gender play in an affirming way. My wonderful mentor, Hadara Bar-Nadav, had this exercise where you have to write a speaker from a different gender. And during that exercise I was like, “Ooh! Wow! That’s doing stuff!” So yeah, art gives us space to play, to try on different personas, different modes of being that might be impossible or extremely difficult to do in life.

CEJ: I definitely uncover a lot more in my poetry than in therapy. In grad school, Camille T. Dungy recommended I go back through my thesis and identify the repeating images and motifs in my work. I found that process more revealing of myself and my relationship to my body than of how I should reorganize the manuscript.

Continuing on with Muzzle, I noticed that your sense of chronology was very open in the books as well—poems about an ex-husband interweave with poems about a wife. Relationships and their timeframes felt quite open-ended as well. When putting this collection together, what was your process for ordering the poems in relation to one another?

RC: Ooh, that’s a really good question. After I had about a manuscript’s worth of poems, I tried to find a way to narrative-ize what I had. The narrative I settled on makes absolutely no sense when you’re reading the book, but it helped my brain during the process. I organized the poems as a kind of Schrödinger’s family where everyone is trying to figure out if they’re dead or not. I thought messing with time would be an interesting way to convey that. It’s not so much a chronology as an association. When I’m ordering poems in a manuscript, I’m really a cliché trans girl—I like DJing, making playlists—so that bled into how I conceptualized making a manuscript.

Actually, when I was at AWP 2014 in Seattle, I went to a panel on ordering manuscripts, and the Graywolf editor suggested thinking of each manuscript as a poem in which every individual poem is a line in the larger piece. So some of my poems have this really high energy, others rest; there are spikes. So I was actually asking myself, “What do I need to do to lead the reader up to these spikes and then lead them out?” I think about where I can put handholds, footholds, and how productive those touchpoints are for the reader.

CEJ: Let’s delve a little more into the organization of the book. The major themes/images of your collection include animality and its restraint/release, hence the title Muzzle and the four definitions you frontload at the beginning.

What came first: the multi-meaning theme of the muzzle, or did the poems themselves begin converging around the image of the muzzle? What did you enjoy about drawing out this theme?

RC: Originally, this book had a really terrible title. So bad, it was called “Apocalypse with” and a lot of the poems were titled “Apocalypse with X” or “Apocalypse with Y,” etc. I shared it with some early readers and they were like, “Don’t do that.” At that time, I was also really enamored with Matt Rasmussen’s Black Aperture, which is largely about his brother’s death by suicide and includes these repeated images of muzzles, guns, bullets, holes. So I looked at my own manuscript and thought, “Okay, I have some hunting poems, some dog and wolf poems, lots of mouths, a lot of teeth.” I also thought one-word titles were very cool at the time, so I began brainstorming a bunch of words that might fit and I eventually landed on Muzzle.

I also was reading Natasha Trethewey’s Thrall and watching her interview about the book. She was talking about how she came up with the title. In a previous collection, she was using the word “thrall” and had looked up the definition, all its uses. I then went to the definitions of “muzzle” and it really helped create structures to help me jump from one draft to the next. I thought about how the definitions could be organized as a progression, creating an intention behind all these various forms of violence and tension I’d been working with.

“The domesticity softens the violence, and yet connects the two.”

What was important to me when titling different drafts “Muzzle” was the role of aggression and the threat of violence becoming linked to domesticity and traditional heteronormativity. In the first couple of “Muzzles” you have people hunting an animal that was once a person—someone’s son. You have a car wreck, followed by grocery shopping with a baby. You have a scene of teaching a daughter how to drive. It’s all of these associations and juxtapositions—the domesticity softens the violence, and yet connects the two.

CEJ: You also have a lot of poems titled “Faithful is The Wounding” in this collection, can you tell me about those? What led you to connect them?

RC: I wanted to be a little looser with “Faithful is The Wounding.” I really enjoyed using repeated titles in this book and I think it’s fun to encounter them in other people’s books too.

“Faithful is The Wounding” as a whole is a series of poems about a husband and wife doing kind of mean things to each other. I took inspiration from Monica Youn’s Ignatz, where she draws a lot from this old comic called Krazy Kat—a precursor to Tom and Jerry. I wanted the speakers to be mean, be victimized by each other, without there really being lasting consequences.

CEJ: Kind of like your poem in which the speaker puts her ex-husband in a crate and drops him off in the woods. That is definitely my favorite divorce poem.

RC: Sometimes you just gotta put your exes in crates and take them out.

In his carrier, my husband

pants and spins. He howls

as we curve around country roads.

Soon, trees replace houses; we are alone.

I carry my husband into the woods.

When I reach a clearing,

I put him down. My husband

tests the dirt with his hands, his nose.

He whimpers. Go, I say, I don’t want you

anymore. He looks at me, and we know

when we see each other again

he will bare his teeth.

(“Faithful is The Wounding,” 18)

CEJ: This segues well into my next question: Muzzle blurs the line between the animal and the human, especially in one of the many poems titled “Muzzle”: “They aim at a wolf, / who, a second ago, / was someone’s son” (2). How do you see your own (and others’) humanity and animality?

RC: Outside of poetry, I’m a big softy for animals. I have a pet pig and I watch him go through his day and he gives me a lot to reflect on about how I approach the world, and how similar we are. Maybe it’s because I got him as a piglet and he inherited like, trans-species neuroticism [laughs].

I think there’s a lot of humanity, or I guess, personhood, that animals have. And alternately, there’s a lot of animality in how people go about treating each other. That’s another hierarchy I’m interested in destabilizing: who is the animal, who is the person, who holds power and who doesn’t? In a sense, human and animal have become a shorthand for looking at different power dynamics between individuals.

CEJ: Yes, that’s definitely an interest of mine as well. It makes me think of Gabriel Gudding’s Literature for Nonhumans [out of print] and John Berger’s essay “Why Look at Animals?”

Next question: At times your poems are deeply rooted in the body and other times they feel disassociated. Has your writing process changed your relationship to your body?

RC: No, not at all. I wrote and did a bulk of the editing on these poems when I was largely disassociating from my body, and it was kind of a mystery to me. Yeah, there’s some biographical stuff, like coming to terms with and naming past experiences as sexual assault, and growing up, how it was implied that that sort of stuff doesn’t happen to AMAB people. So there was a lot of unlearning about what that means, how it’s impacted my life.

“In my experience, part of transitioning means that it is so much less work to be a girl. It’s just what I would normally do.”

Then, of course, there’s gender identity and not knowing why I didn’t feel comfortable as a masculine-presenting person. Like, why was it so hard to just exist as a normal person? In my experience, part of transitioning means that it is so much less work to be a girl. It’s just what I would normally do. I don’t have to do all these backflips and translations of what I want to say or how I engage with the world. And not to beat a dead horse, but it’s kind of like—embodiment, disassociation, there are all these juxtapositions between binaries: your mind, your body, your body, your mind. The reality between those distinctions isn’t clear cut. So having these poems split between those two registers helps me conceptualize what I want those poems to do.

In short, myself and I think a lot of other people experience these moments of intense embodiment and then intense disassociation—like disjuncture within our own bodies. And I like playing with that. I feel like that's like a fun space to write from. Maybe ‘fun’ is the wrong word, but I think it can be the right word, though.

CEJ: Okay, final question: What do you want readers to take away from Muzzle?

RC: Probably that interpersonal relationships are complicated, and usually there’s not a clear-cut distinction between who’s being hurt and who’s doing the hurting. Of course, there are extremes, but like for the most part, in day-to-day interactions, it’s all contextual about how you see people interact. There’s a tendency to assume that when we solidify things in writing, it’s like we have a thesis about which characters are in the wrong and which characters are in the right. And I think it isn’t that straightforward. Complicating how we write about violence and transgression can help us understand individual relationships more fully. In “Negative Capability and its Children,” Charles Simic argues that one of poetry’s greatest ambitions is thought without recursion to abstractions, logic, and categorical postulates. Making things fluid can help us think better, understand each other more deeply.