Bitch, This Happened: Pregaming with Danielle Chelosky

Rachel A.G. Gilman and Danielle Chelosky discuss the allure of self destruction, the shifting boundaries of memoir, and Danielle's full-length debut, PREGAMING GRIEF.

I read Danielle Chelosky’s full-length debut Pregaming Grief in a few hours on a flight back from London, after a trip where I’d lost the plot on what I wanted from life. My first reaction to the book was to scream in the airplane bathroom. My second was to consider breaking up with my boyfriend.

When I shared this with Danielle, she was flattered. Best review, she replied. I’m going to make t-shirts (these, alongside tote bags, are now available for purchase on her website).

I’ve been a fan of Danielle’s work for a while. With her astute observations on new music in her journalistic writing as well as heart-wrenching poetics in chapbooks show me your face and cheat, she is one of the only people born in the 2000s that I’d actually want to get a drink with. My admiration for Pregaming Grief finally made that happen.

We meet up on a January Friday at Lucky Dog in Williamsburg, a place which allows entrance to canines alongside their owners. It’s a prelude to attending the Dirt Buyer show at Baby’s All Right. Admittedly, given Danielle’s love of emo music, I’d worried this plan could mean a lot of moshing, something that had exited my life somewhere between my early and mid-twenties. After listening to the group’s latest record, though, I felt safe. People who listen to slow, depressing as fuck emo-folk don’t strike me as the same crowd who wants to rage.

Danielle is sitting at the bar when I arrive. She’s reading Michel Houellebecq’s Serotonin, her long, dark hair falling down her back. A ginger ale keeps her company. Danielle doesn’t drink anymore, but she still enjoys talking in bars, slipping out from time to time to chain smoke. If she ever goes to Paris, she fears, she would start again, solely based on what she’s read of Anaïs Nin and Annie Ernaux’s journals, two of her greatest influences (Ernaux is quoted in Pregaming Grief’s epigraph).

“I’ve never been interviewed before,” Danielle tells me. Heavy glitter lines her blue eyes, some having fallen onto her freckles.

“Are you uncomfortable?” I ask.

“I don’t know.” She pauses. “Time will tell.”

I doubt this will be her last interview given that Pregaming Grief was featured in Nylon months ahead of publication, a rarity for indie releases. The book is equal parts literary and diaristic; a dark, dreamy blur of speeding cars, confusion, and loss. It inhabits a place where the way that someone shows their love is by keeping you in their peripheral vision. It’s painful, it’s provocative, and it’s pretty goddamn perfect.

[Pregaming Grief] is equal parts literary and diaristic; a dark, dreamy blur of speeding cars, confusion, and loss. It inhabits a place where the way that someone shows their love is by keeping you in their peripheral vision.

Danielle had always wanted to write a book. It wasn’t until the winter break of her senior year at Sarah Lawrence that she actually began digging through her Google Drive and realized she had enough to assemble a manuscript. She rushed to put it together and sent it to Elizabeth Ellen, with whom Danielle first connected in 2021 when submitting to Hobart.

“I sent her a Fucked Up Modern Love Essay, and she rejected it,” Danielle says. “I was really angry, like, ‘Why?’ After she told me, I fixed it and sent it back to her the next day. Then she was like, ‘This is so good it made me cry.’”

This was Danielle’s first lit mag acceptance. She’d always hoped to get involved in the scene, but there hadn’t been many opportunities in her Long Island high school. Although she doesn’t consider herself good at academia, it was her assigned readings at Sarah Lawrence that helped pull Danielle into the alt-lit world and allowed her to discover writers like Chelsea Hodson and Melissa Febos. Now, she serves as an editorial assistant at Amphetamine Sulphate as well as an editor at Hobart under Ellen.

“Elizabeth and I have a very special kinship,” Danielle says. “We have a lot of things in common, which are probably really self-destructive things.” She laughs. “She’s a little more chaotic than me.”

Ellen accepted Pregaming Grief immediately, but it took two years for Danielle to edit and finalize the book. “She got pissed off at points and was like, ‘What are you doing? This is not the book I accepted.’ And I had to say, ‘I know, I know. Just trust me, it’s going to be better.’ I get this impulse to constantly edit and make it more accurate. It’s hard to make it a perfect to match reality. It’s fucking impossible.”

Pregaming Grief begins as Danielle exits a long-term relationship that has deteriorated due to addiction. She soon enters into something new with someone else, something that feeds on a different kind of self-delusion traveling the path to self-destruction. The liquor, the men, the heartbreak, the mania, the isolation, she writes. The memory is disturbingly bright in my mind, overexposed. The narrative is frequently directed at the man from Danielle’s first chaotic relationship who she refers to as “you.”

“I used to do that a lot whenever I was writing about a guy because usually they have really generic names,” she says. “I just love the way ‘you’ sounds.”

Most, if not all, of the names used in the book are fake, which was a difficult choice. “First, I was just doing letters for characters, and it was unreadable and confusing. For a short piece, maybe that works, but for a book, it’s like you’re talking about the fucking alphabet,” she says. “It’s nauseating.” She wanted to emulate her idol Chris Kraus in I Love Dick with the use of everyone’s real names, but ultimately decided it wasn’t worth the risk of retaliation.

The name conversation, however, does beg the question of the book’s genre. Is it a novel, a memoir, or something in the land of autofiction? The last term makes Danielle cringe.

“I feel like in the alt-lit scene, people don’t say memoir that much,” she says. “And also, I’m twenty-three, so memoir feels kind of weird. It’s just two years of my life.” What is most important to her is that readers know the events are all true. “I don’t want people to think it’s fiction,” she adds. “Like, bitch, this happened.”

One of Danielle’s friends in Pregaming Grief quips to her that she thinks Danielle too frequently flirts with catastrophe. Similarly, a former love interest tries to remind her, “You don’t need to have bad forgettable sex so you can immortalize it in writing.” Neither of these comments are inaccurate, especially given the number of abandoned places explored, car problems experienced, and losers screwed.

Danielle admits to me that she wasn’t sure how some parts of the book would associate with each other (her interest in abandoned buildings, for instance, was simply because she was “bored and angsty as fuck”). To me, though, her varied attempts at toying with danger feel more like a comprehension strategy than a display of recklessness, especially for a person who admits she would fail multiple choice sections on a test but ace the essay portion. The chaos is in multi-dimensional pursuit of understanding ambiguous relationships, with men but also with the world at large.

“I think part of why I was interested in older guys was because I knew I was young and I wanted to prepare for the years ahead of me. I thought I could learn from them. But then I realized that they didn’t know shit.”

What does it mean to drift through college classes feeling lost, empty-headed, and insecure as people around you waffle between whether someone is nice or more of a robot? How can you love someone when you haven’t even been outside together, worrying that all of your relationships will feel like museums: places you briefly look around but ultimately depart? Why has the middle ground suddenly disappeared, making everything seem like life or death, bliss or agony, the ideas overlapping so brutally that they become indistinguishable?

These questions are huge, especially for someone Danielle’s age. In Pregaming Grief, she is aware enough to know she is getting to the point in life where she’s going to start hating it, but she also doesn’t feel like a grown-up given that she can consent to sex yet can’t legally drink. While she takes Plan B for the first time, she’s also having to hide where she’s going from her mom. As she rushes to collect experiences, she’s also sitting through older men telling her about their twenties before even entering hers. Again, the world is in constant contradiction.

“Everyone views age differently,” Danielle says to this point. Most especially, she’s found people have varied reactions to the gaps between her and boyfriends. “I don’t even know how to write about it. It’s hard to navigate because it’s such a complex dynamic. I think part of why I was interested in older guys was because I knew I was young and I wanted to prepare for the years ahead of me. I thought I could learn from them. But then I realized that they didn’t know shit.”

“Everyone is a writer, but most people suck.”

All of the men in Pregaming Grief seem to know shit; not just Danielle’s two primary dysfunctional partners but also the others with whom she endures endless wine and pizza and fucking. The worst of the group is Ben, who doesn’t have the courage to tell Danielle he’s in an open relationship but does feel comfortable talking about it on his podcast.

“At one point, we were hanging out and he was suspicious that I had COVID because I had a cough,” Danielle tells me. “I’d driven all the way from Long Island to Brooklyn to see him, and he said, ‘The only way we’re doing it is if it’s doggy style and we’re both wearing masks.’” She instead chose to stomp away and go home.

Some of the brokenness of these partners felt to me like a result of Danielle dating everyone during “the plague,” which is how the height of the pandemic is referred to throughout Pregaming Grief (“Pandemic is not a pretty word, and we’re tired of hearing it,” she says). From my own experience on the apps, it was a world where it became normal for people to treat others poorly. Danielle thinks it speaks more generally to dating in New York. She had a different experience when she left the city last year for a short stint in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, as well as when she got off the apps entirely this year after moving back to Long Island.

“It’s so demeaning, like any social media,” she says. “It feels like you’re shopping while also trying to sell yourself.” Her decision to get sober also came after a long time of using apps out of a bored desire to get drunk and have fun. She was tired of it feeling like a chore. “I was scrolling through TikTok recently, which I shouldn’t have been, and there was a post that said, ‘The fear of when you want to hang out with him sober,’ because I guess that means you actually like him. I was like, that’s bleak as fuck.”

Despite having a fairly negative attitude toward social media, Danielle is quite popular on Twitter/X with more than 10,000 followers. I half-jokingly refer to her as the Emo Princess of the app and later see it worked into a book promotion graphic. In addition to her writing, Danielle also uses Twitter to promote her work at Stereogum. “I’m lucky that I make money off of listening to music and writing about it,” she says. “I get to interview musicians all the time and that really helps because I get to hear about their processes and then I’m like, ‘I’m going to steal that, thank you very much.’”

The two worlds often intersect, and not just in Danielle’s playlist for the book. Pregaming Grief frequently ponders what it means to be a writer. Do we write in search of solutions? Attempts at revenge? When one ex warns Danielle not to lose her mind for a three-thousand-dollar book advance, she retorts, “Why not? I do it every day for free.” I’m most fascinated when Danielle concludes that she became a writer because it was the art form that offered the greatest amount of immediate gratification.

“Everyone is a writer, but most people suck,” she says, twisting a plastic straw in her mouth.

I can tell she wants a cigarette, another moment of instant pleasure at her fingertips. Our on-the-record is coming to an end.

Pregaming Grief concludes with something of a cliff hanger, Danielle returning to one of her toxic relationships. That’s not the full story. “I had written a whole section about what happens after the current ending, like 10,000 more words, but I knew Elizabeth wouldn’t let me throw it in,” she says. “She really liked the original. With on and off relationships, you never really know when it’s over.”

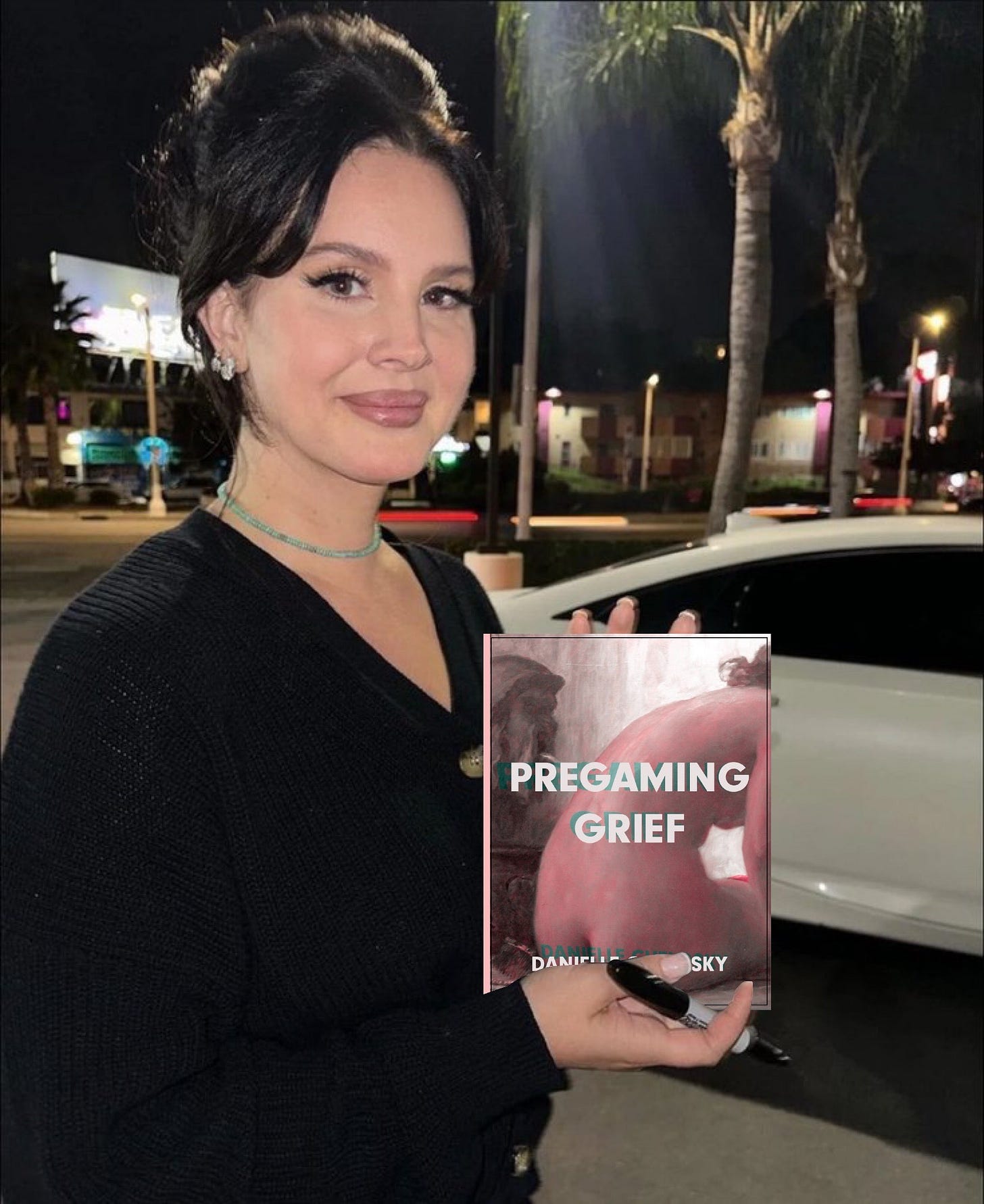

Given that Danielle is already working on a sequel, readers will likely get to know everything in due course. For now, though, she’s focused on what it will feel like for Pregaming Grief to be out in the world. “I’m excited to hold it in my own hands,” she says, beaming. “I’m excited for it to be a physical object.” She’s also staying grateful for the little things. “Whenever I feel bad about something lately, I think, ‘At least I haven’t hit someone with my car,’ and it makes me so happy.”

“Have you come close?” I ask.

“That’s not important. Hitting other cars, that’s not so bad. But hitting a person? You can’t come back from that.”

Her impatient streak also has her trying to sell her next book: a deranged literary thriller novel about an epileptic girl who tries to communicate to fellow epileptic Ian Curtis from Joy Division through her seizures. It’s the book she wrote while considering working in publishing, and ultimately the book she wrote instead of dealing with the politics of the industry. All in all—from my position, working in publishing—I’d say it was probably the right move.

“I’m querying agents now,” she says. “I am fucking getting money for this shit. I don’t care.”

After this statement, the opening notes to “Love Will Tear Us Apart” begin to play over the bar’s speakers. Danielle and I look at each other, jaws dropped. Even Emo Princesses aren’t immune to a perfect, metaphorical moment. It’s hard not to smile, too, as she bops a little to the song, especially knowing she’s going to turn the coincidence into content when she tweets about it later.

“Holy shit. I just summoned that,” she beams. “I’m so getting my $300,000.”