A Daily Occurrence

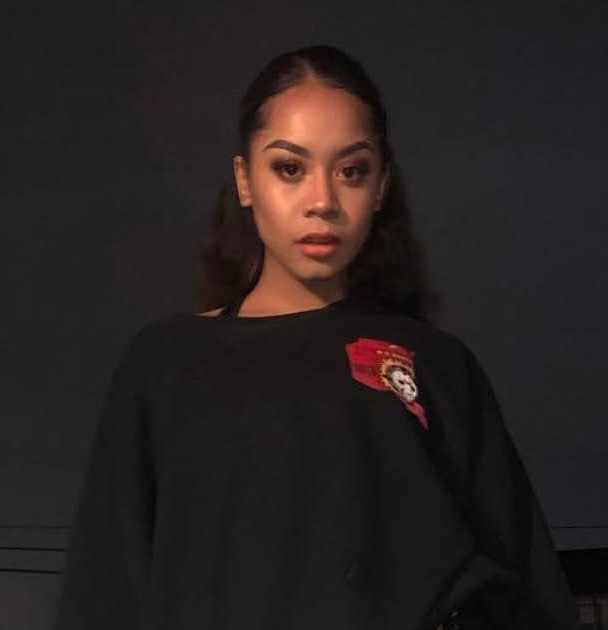

Lanae Tipton and Marissa Leanne Potts on living with sexual violence and abuse in prison.

I. Lanae

My stomach unleashed a deafening growl upon hearing the roll and rattle of an approaching food cart. Having spent the last three of fourteen days in isolation punishment at the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, I was famished. Up until that point, my meals had consisted solely of two bologna sandwiches.

A male officer’s face appeared at my cell door and smiled menacingly through the metal mesh grate as he opened the slot where the sandwiches are usually dropped, but today he produced a hot tray. Two steak-and-cheese-stuffed burritos from the officers’ dining hall sat in front of me, the prison equivalent of a five-star meal. My stomach roared in agreement to the aroma, then dropped as I heard the officer utter his demand.

“Get naked and dance for me and you can have it,” he sneered. Gaping at him, disbelief and hunger shone in my eyes as he added, “Or get nothing at all.” So I ate my fill that day, burning in shame.

A similar thing happened to Angela. She was two months away from going home after almost fifteen years of imprisonment. She was so close to freedom when she was suddenly forced to defend herself against an attack by her roommate. After the altercation, Angela faced a disciplinary infraction that could jeopardize her release. When she explained to the investigating officer that her impending freedom was on the line, he offered her an ultimatum: to prove how bad she wanted to go home, she needed to perform a sexual favor. Otherwise, he would see to it that she was disciplined for getting into a fight, and therefore risk postponing her release. Angela is now home with her children.

When she explained to the investigating officer that her impending freedom was on the line, he offered her an ultimatum: to prove how bad she wanted to go home, she needed to perform a sexual favor. Otherwise, he would see to it that she was disciplined for getting into a fight, and therefore risk postponing her release.

Stories like this are typical for those who are incarcerated. Survived + Punished, an organization aiming to eradicate the criminalization of domestic and sexual violence survivors, reported that in 400 documented cases of sexual misconduct by an authority figure, only 25% ended with the offending officer being held responsible. As discouraging as that statistic is, it’s even worse for incarcerated people, since most incidents of abuse are never reported in the first place due to the fear of retaliation. Another reason victims remain silent is so they can continue to receive contraband products, like drugs or makeup, that officers smuggle in as a form of hush money.

Moreover, when they do report abuse, incarcerated victims lack support. Rather than being taken seriously, they instead are faced with intense scrutiny of their stories and/or given harsh punishment, like having their property confiscated or being placed in isolation. Their communication can be monitored, personal property sifted through with a fine-tooth comb, and contact with their families forbidden until an official investigation is completed.

Meanwhile, while sexual abuse ends up mostly being hidden behind cell walls, physical abuse by the prison staff occurs regularly and out in the open. However, it’s often covered up by officers filing false reports, claiming that they were driven to use force against their victims. For instance, if someone is deemed disobedient or uses a tone of voice that’s perceived as aggressive, it can result in a response team of 5-10 mostly middle-aged male officers with military experience showing up to discipline the alleged offender. The officers are allowed to rough up incarcerated people by slamming, tackling, or forcefully restraining them if they think that they’re acting out of line. After these excessive displays of force, victims often require stitches, have black eyes, broken teeth and bones, and on top of all that receive a disciplinary case that labels them as the aggressor and justifies the officers’ abusive tactics.

For many women who are incarcerated, this traps them in a vicious cycle of abuse. Statistics show that 94% of the women’s prison population have a history of sexual or physical abuse prior to incarceration. Many women ended up in prison because they seriously harmed, or in some cases killed, their abusers in self-defense. Not only do they face punishment for attempting to escape their abusers, now they’re trapped in a violent prison system, available to be victimized again. Only this time, it’s at the hand of abusive officers, without any ability to escape.

Our society falsely believes that if we banish someone to prison, brand incarceration as rehabilitation, then that person will come out reformed by the experience. However, I can tell you that the opposite is true. Prison is not a sanctuary, but a hostile environment permeated by violence and abuse, leaving hardly any room for anyone to recover from past traumas and make a real effort to rehabilitate themselves.

When I asked five officers whom I interact with, all varying in title and rank and all with more than ten years at TDCJ: How do you believe prisons help rehabilitate victims of abuse? Their answers were identical. They all think that the programs that are made available will rehabilitate the people who are incarcerated. However, the few classes offered at TDCJ are only accessible if you have a record of good behavior. This programming includes parenting classes, various Christian-based classes such as life skills, and a drug-related class. But, there are no classes for survivors of domestic violence or trauma from past abuse. I believe that in order to help people heal and rehabilitate, any class promoting positive change should be a core, fundamental offering to anyone who requires it, because without access to that kind of program, there are no other positive outlets.

Abuse has permeated women’s prisons for decades and continues to plague the people within its walls, especially those who remain haunted by their pasts. These ghosts linger among many women like myself, who have gone from one life of abuse to another, now riddled with hired abusers that keep us looking over our shoulders.

What incarcerated victims of abuse really need to heal is an actual sanctuary from abuse and intimidation, not further harassment and punishment. We need a confidential, safe, and helpful process for reporting incidents against staff that won’t treat us as the aggressors. We need the prison system to hold abusive staff accountable, and for staff to see the incarcerated as people, not prisoners. Lastly, victims of abuse need to learn useful coping mechanisms to help navigate past and present traumas and build resilience. If we can receive all these things, only then can there be true rehabilitation.

—Lanae Tipton

II. Marissa

As a kid in fifth grade, I was taught multiplication, division, and geography. I was educated about bodily changes and menstrual cycles. Videos about stranger danger and hugs not drugs soon followed.

I never learned about the red flags of abuse, or the types of behavior that are considered abusive. This ignorance contributed to me being incarcerated at 26 on the Lane Murray unit in Texas.

Fifteen years after those classes, I find myself sweating outside the prison administration building, awaiting punishment for being “Out of Place.” This is because I returned to my previous housing area for items I forgot there without permission, because I knew it wouldn’t be granted.

Watching an officer guide inmate traffic to and from the chow hall, I yelled, “Sir, can I get in line to eat, then I’ll come back to be read my case?”

“Shut up bitch, you refused chow when you fell out of place.”

I began to boil on the inside. It wasn’t my first time being degraded by an officer, and most likely wouldn’t be my last. That didn’t mean I would tolerate it, though. Having a Texas Department of Criminal Justice number with an offender status didn’t take my humanity away.

“Hey, you don’t talk to me like that. I—”

I was interrupted by fear as the guard stormed my way. The man who had taken a legal oath to be responsible for my safety on TDCJ grounds approached me with balled fists and an enraged face. A familiar feeling came over me. I recognized it as a PTSD response from my abusive relationship with the father of my six children, developed over six years of mental, emotional, and physical abuse.

In my opinion, if the government would divert some of the money they use to incarcerate us towards adding intimate partner violence education into school curriculums, then maybe I wouldn’t be where I am today.

Studies show that roughly 80% of women entering into the prison system have experienced intimate partner violence prior to incarceration. The lack of education about abuse plays a major role in the vicious cycle of violence in relationships. That cycle continues when victims are criminalized and punished with a prison sentence.

From the beginning, I didn’t know about coercive violence. After entering into an abusive relationship and staying until I couldn’t, I was criminalized for my abuser’s crimes, then placed into a system built on the same violent tactics as my unhealthy relationship. How is placing me in an environment that follows the same playbook of the one I escaped any better for me or society? I am trying to rehabilitate. Where can I find the space to learn how to set healthy boundaries in here, when I still have to walk on eggshells and watch everything I see, say, or do?

It’s like trying to build with the same broken bricks from a foundation that didn’t work the first time.

In my opinion, if the government would divert some of the money they use to incarcerate us towards adding intimate partner violence education into school curriculums, then maybe I wouldn’t be where I am today. Not only would it stop the bleeding, it could prevent the cut altogether.

Right now, prison isn’t a place for healing. You can learn to be a better criminal, or to remain a silent victim.

—Marissa Leanne Potts