The Price of Belonging to You

Heather Domenicis on the somatics of motherloss, fatherloss, and Chelsea Bieker's MADWOMAN.

2017: I am twenty years old and not into wellness, just into drinking weekends away and blacking out memories of the parties I attend—fuzzy scenes of hooking up with boys, kissing girls and wishing it were more. I am still physically healthy. I no longer read for fun, just for school. I am in an a cappella group. I smoke weed every night in the woods off campus with my boyfriend after theatre rehearsals.

I get good grades, always have, but I am still trying to convince myself that I am smart. I have given up on trying to fit in at this wealthy college. The first week of freshman year, our sociology professor lines us up in front of the library steps and asks us to take a step up or down, depending on how we answer a series of questions about our privilege. I end up at the bottom. I have a hard time holding onto female friends but hold onto boyfriends beyond their best by date. I am confused. I miss my Dad and am just beginning to write about it.

During my shift at the college library circulation desk, my phone buzzes. I have a Facebook message request and three friend requests. One from you, Mother, one from your husband, and one from your mother. I open your message:

this is your mother now I want to know if you feel like talking to me, if so let me know and I’ll send you a friend request or vice versa, you are so beautiful, you look a lot like me!

Nothing menacing. A nice message, but I haven’t seen you since I was four, when you showed up on our doorstep, pregnant and wanting something, and someone sent you away. I waved goodbye to you in our driveway and wondered how you could be having another baby when you could not even take care of me. Sitting here with your words in my hand, I wish I could hand them back to you and tell you to never hit send. I cannot fathom how we’ve arrived here.

When

first posted about her new novel, Madwoman, I knew I’d want to write about it. I had too much in common with the protagonist, Clove, not to: motherloss, communicating with an imprisoned parent via snail mail, being found by an estranged parent, dissecting memories to piece together a puzzling childhood, and diving into wellness trends to undo all the trauma of your past.Like Clove, I’ve “done my best to be untraceable” so you would never find me like this—so I could find you on my own terms someday. My Facebook name is listed as “Heather Lynn” so a Google search won’t turn me up. But, there are footprints: a couple small publications, a few full name drops from random summer camp newsletters, named pictures of me in a curly red wig playing Annie in middle school. Despite my best attempts at damage control, I exist online. I click on your profile picture, stomach churning, heat climbing from my heart to my cheeks. You sit on a stool in a dull white tank top, overweight, you look sad, not smiling. Wood paneling behind you, chunky overgrown highlights streaking your dark hair. Your thin lips are mine. Your big eyes, mine. Or vice versa. My features are yours. You’re in my face, my limbs, my stance. I over-pronate like I’ve heard you do, but I was spared the true knock knees you apparently have. I run to the head librarian and tell him there’s been a family emergency, which is not untrue. This feels like an emergency. My body certainly thinks it is.

In a stairwell, I look up the counseling center’s hours. No walk-ins right now. The webpage offers an alternative—speak with a chaplain! I am not religious, I quit carrying the cross and serving the altar back in high school, but there is nowhere else to go. A short while later, I find myself in the office of a strange woman with kind eyes. She shuts her door and I explain it all. She is motherly, helps me slow my breath, gives me water and tissues, and we talk about whether or not I want to respond to you, Mother. I think about it for an insignificant amount of time before deciding, no, I will not respond. It seems scary and stressful. With school, my work-study, and all my extracurriculars, I do not feel as though I can take on any more.

“Where, Mother, was the time for me to deal with you?” Clove asks herself as she looks around at the life she has painstakingly handcrafted to be the opposite of what her mother offered, or couldn’t offer. I look around at this nice room in this nice building on this prestigious college campus. You birthed me in a jail and now I am here. I have done it all without you, so why should I respond? You didn’t even use proper grammar. Out of sight, out of mind. I am taking a practical approach. I tell myself I will reach out to you when I am older. A post-grad adult. “You can see, Mother, why it’s easier to try to not think of you at all.”

We learn Clove’s story through her attempt at writing back to her imprisoned mother, who has just asked her for help getting a retrial of her case. Now that the #MeToo movement has taken off, her mother hopes to convince a jury that she is, in fact, not guilty of killing Clove’s father, who incessantly abused her. While her mother sits in a jail cell, Clove has remodeled herself into a reinvented woman: a wellness-obsessed Instagram momfluencer with a remarkably stable family who is “addicted to self-improvement, each new supplement pulling me further away from my past.” While Clove’s past is vivid with memories of domestic violence between her parents, mine was filled with other dangers, yet still shrouded with mysteries. Father, what visits with your friends that I tagged along to were really drug deals? When were you really “sleeping at work” and when were you actually out all night, hiding your drug use and hiding yourself away too? And where did my Mother go? Was she really in Missouri or was she just on the other side of our little beach town?

Despite her over-commitment to wellness trends and tendency to overspend at her local natural grocery store, Clove is like me in that her body is constantly stuck in fight-or-flight mode—the things she has seen have “created a barrier between me and the living world, and there is nothing I can ever do, no supplement I can take, no inner-child meditation strong enough, deep enough, to remove it.” Though our brands of family trauma are different, I felt called out more than once while reading—I too have tried binaural beats and “Vitamin D3 now with K2.” So many of us—people with fucked up childhoods—are stuck in this parasympathetic state, creating confusing emotional responses and even sometimes wreaking havoc on our physical bodies, manifesting in the form of chronic pain or other illnesses. Motherloss is almost like fatherloss and fatherloss is almost like motherloss, different but the same. And Clove and I have both, two abandoned women struggling to make sense of this world, reckoning with how our new and old lives may or may not fit together. Does my motherloss hang in the air the way Clove can detect it in people she meets?

We’re both trying to move forward, but our parents keep interrupting.

When I check the mailbox at Auntie Karen and Uncle Bob’s house, I find a letter from you, Father. I am eleven, twelve, thirteen, but I am not shocked. You live on Sunrise Highway, a place that sounds magical, but underneath your address is a neon pink stamp that says Prison Generated Mail.

You exist only on a page, and very occasionally through a scratchy telephone line. You exist in my mind, in memories of the past, memories of California. Memories of beaches and bike rides and swing sets and car trips, the time you drove me to the emergency room when I fell out back and there was a bloody gash on my forehead. A memory of you staring down at me and telling me everything will be okay while the doctor placed stitches. Sometimes I am slow to write back because I am consumed with middle school: theatre rehearsals, Tae Kwon Do practice, and memorizing every detail I can gather on my current crush, Kyle or Sam or Josiah or Caz.

Our letters are simple. I ask you what it’s like in there. You draw a diagram of the dorms, another of the yard and the track. You tell me you bought a Yamaha guitar to learn but it hurts your fingers. You say you miss me. You say you love me. You recall old memories, like the tree I used to climb in the preschool parking lot when you picked me up. I recall old memories of you being late to pickup or you unable to wake up in the morning. I recall sitting in the principal’s office and her telling me I should jump on you to wake you up in the mornings, because I couldn’t be late anymore. I remember doing that, and your anger. I keep these thoughts to myself and write them down years later, in my twenties.

Sometimes you quiz me on Spanish vocabulary and teach me words you are learning from other inmates:

Espero. I wait.

Esperas. You wait.

Esperando. We’re waiting.

Estoy listo. I’m ready.

And your favorite: Te amo que más a mé vida. I love you more than my life.

You write: I wish we could go back in time, so that it didn’t turn out that you are there and I am here…I am sorry that it is like this right now. I miss seeing you every day.

Clove, as she reads her mother’s letters pleading for help, thinks: “Your handwriting, your sadness, your need, your intense pulsing need.” I didn’t register this at the time. I let your letters roll off my back and buried any inklings of feeling. Rereading your letters now, it is so apparent, so in my face, how much you needed me. How blind I was to it. A festering guilt over our lack of relationship now.

I wonder, but do not write back: If you love me more than your life, and drugs are your life, then why are you there and I am here? Why can we not go back and make different choices? By we, I mean you. Would you consider me this time, if you knew what was coming?

Clove, while spiraling, finds herself “in the sordid world of our headlines, the many articles and message boards and photographs starring my father’s death.” On choice nights, I find myself there too, especially as I try to write you alive, Mother. I will always regret not responding to your Facebook message. I told myself I’d do it after college, but you died the next summer, after my sophomore year. I learn of your death through a text from my father. The audacity to send just a text. An infuriating symbol of his consideration.

I find only a couple articles, your death quieter than the scene with Clove’s parents.

(Cadet, MO.) A man from Cadet, 40-year-old [REDACTED], is charged with driving while intoxicated—a chronic offender charged with involuntary manslaughter in the first degree after a traffic accident last August in which his wife, Barbara, was killed. [REDACTED] is also charged with second degree assault and driving with a revoked license. The wreck took place just after 11 o'clock Sunday night, August 5 of 2018 when Barbara was a passenger in a car driven south on highway 21 in Washington County at Tindall Road by [REDACTED]. The car crossed over the center line and crashed into a car driven north. Barbara was pronounced dead at Washington County Memorial Hospital. [REDACTED] sustained serious injuries. The crash was a head on collision.

I find the mugshot of your husband, who fathered one of your children. This is the man who sent me a friend request the year before. Looking at him calcifies my heart. What did he do to your heart, Mother?

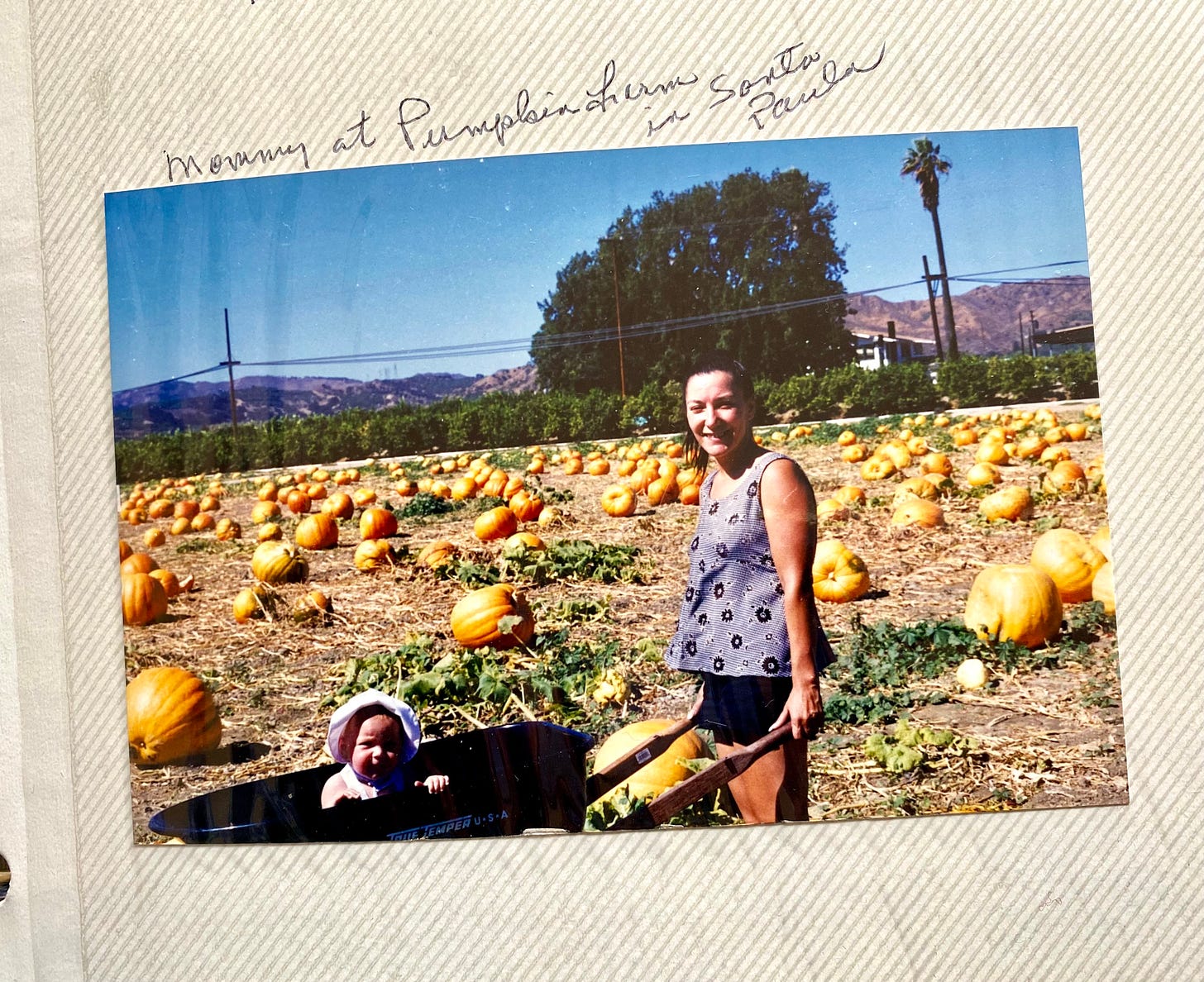

Later on, in my twenties, I ask some of my half-siblings what really happened. I suppose everything is hearsay. I didn’t attend the trial. But I hear of a fight that night, an injury so bad that he decided to drive you to the hospital, drunk. Clove talks about the short-lived honeymoon periods of peace after her parents’ fights, when everyone holds their breath while savoring the happy fleeting feelings. Years ago, you posted a mirror selfie with your husband, flowers on the bathroom counter and the bed behind you. A honeymoon high spot? I do not know if any of this is true, if you lived these ups and downs. But I know I am happy to not have witnessed any of it. Sometimes, I am thankful to not have known you. I like to imagine that everyone was kind to you, but that is because you exist only in a fantasy I’ve created from photos. You in your lace wedding dress with my father. You and me in matching outfits. You and me at Mommy & Me swim classes, gym classes. You on a camping trip, glowing, holding a marshmallow on a stick.

I feel a tug to unearth your life, to learn you alive. I’ve never heard your voice. I talk to people who knew you. I have heard that your life began and ended with abuse. Your father, the nights, your room. Constant. “I understand...all the ways your behavior could be explained. But my body doesn’t understand those explanations. And my body is angry.” I manage to track down your childhood address in the projects and, nursing my ever-upset stomach, I decide to drive by. All the homes around yours are fully demolished, yours only half standing. Like you willed them to save a piece for me to see before it was gone forever. I go back and look at photos of you from my infancy, from before. “On my screen now, so many years later, I’m startled by the simple clarity that we are, in this way, the same: we both need our mothers, and there’s no way to relieve the need.”

When Clove is reluctant to write back, to help her mother, her friend tells her, “You’re scared of what it means to have her in the same room as you. You’re scared of your mother.” While I’d give anything to be in a room with my mother, to scratch that itch and know her, I am afraid of you, Father. One of the last times I see you: we are visiting Nana in her final months. She is bedbound, stuck in her mind with no escape. You and I barely speak. You look at your phone more than you look at me. I look at Nana and my dog, glad he can provide her with some momentary joy in the aching dementia. Then Nana scratches a scab off her leg and we jump into action, pressing the blood with a tissue and calling for a nurse. We go wash up in her little private bathroom, glancing at each other in the mirror, only making eye contact in this way. “Your hair is long,” I say. You remove your winter hat to reveal thinning gray hair, then quickly replace it. This is the only way we can look at each other. We are scared of what used to be and that we can’t find a way to put it all back. I don’t think we ever will.

I see you once more at her funeral. That day, I am furious at you—for leaving all the planning and initial payments to me, and for being late, and for bringing friends she would have disliked. Even so, at her grave, I hug you tightly. I am a little girl again, not wanting to let go. I don't want to admit that now that Nana is dead, the one thread connecting me to you has been snipped. An invisible umbilical cord finally cut.

2024: I am 27 years old and I live in New York City in a small but beautiful two bedroom apartment. I can see the Hudson River from my shower. I have two dogs, a stable job, a loving partner of four years, and a life-brightening untraumatized stepdaughter. She sometimes asks about my parents. I’ve told her bits and pieces, a story here, a memory there. When Nana died, she tried her best to cheer me up.

I haven’t had a drink in two years, and I prefer it this way. A long day of activity now gives me a hangover. When I stand up, my heart races and sometimes I get dizzy. My inherited over-pronation is destroying my right knee and I often wear a brace. My genetically high cholesterol must now be medicated. I wear compression socks and go to physical therapy. I sleep with a wrist brace and a night guard. Most days I wake up with a headache. I experience anaphylactic reactions for no reason. I take twelve different pills and supplements and drink 2.5 liters of water each day. I am in therapy and see a coterie of doctors. When I can, I boulder and do yoga and Pilates. I still have trouble holding onto friendships. I no longer perform but I still sing at home. I read, and I write.

On good days, when my chronic illnesses allow me a break from the pain, I play with my stepdaughter. I try to let myself become a child again, one without so much weight on her shoulders. I took her to Six Flags this weekend. I told her to scream on all the rides. To let it all out.

I admire the village her parents have built for her, and feel lucky to be a part of it. Still, I find myself longing for that same village for little me. For the child waiting, some nights, when I write and remember and my body flares up, for her mother—and father—to come back to her.

I loved this so much

Just wow. this is so beautiful. To be read this way, interwoven with Heather's own story, is the honor of a lifetime. Thank you for this, truly.